The Graduate

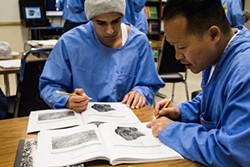

Meet David Nguyen, college graduate and poster child for CR's college campus within the walls of Pelican Bay State Prison

By T.William Wallin[

{

"name": "Top Stories Video Pair",

"insertPoint": "7",

"component": "17087298",

"parentWrapperClass": "fdn-ads-inline-content-block",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

}

]

As the Northern California sunset sinks beyond razor wire fencing and panopticon-style guard towers, David Nguyen reflects on the past 14 years of his life and contemplates the choices that led him to prison. If it wasn't for his attire and surroundings — and the subject of the day — you probably wouldn't suspect he is incarcerated.

Nguyen smiles from ear to ear when he speaks. Standing just above 5 feet tall, his hair is slicked back like a 1950s greaser and he appears meticulously groomed, his tattoos hidden by his long-sleeved shirt. Attentive and articulate, he takes long pauses between sentences, carefully contemplating the right words.

He says he isn't the same person sent to prison at the age of 24 for a home invasion robbery, a crime he now describes as "atrocious" and "horrible." When Nguyen entered the prison system in 2005, he says he had no hope and tried to prove himself by picking fights on the prison yard.

Now Nguyen proves himself in a classroom, having become one of the first two inmates at Pelican Bay State Prison to graduate with an associate degree for transfer through College of the Redwoods' groundbreaking Pelican Bay Scholars Program. Just a few month's shy of his 39th birthday, Nguyen is the first in his family to receive a college degree. He's also become somewhat of an ambassador for the fledgling program, which people say is not only changing inmates' lives, but the very culture of one of California's most notorious prisons.

"He's all about spreading the love and encouraging others to pursue their dreams," says Bernadette Johnson, a CR counselor and the program's first teacher. "He's going to do amazing things when he gets the chance. He definitely has that leadership quality, that gentle lead by example — and courageous at the same time. He's a natural leader in that way and is going to go far in whatever he does."

And that's the very goal of the program: to make good on the promise of rehabilitation that's in the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation's name by preparing inmates to succeed in life on the outside.

"Sometimes, as a society, we forget about them getting out and we only see an incarcerated person," says Pelican Bay Scholars Program coordinator Tory Eagles. "Most people incarcerated will be released someday. At (what) point do we give up? I think that's a critical moment for us in society. I think everyone has the potential to grow beyond the mistakes they make. Programs such as college provide that opportunity."

Until very recently, opportunity was not a word people associated with Pelican Bay.

According to Keramet Reiter, author of 23/7: Pelican Bay Prison and the Rise of Long Term Solitary Confinement, the prison, opened in 1989, was "designed to keep California's alleged 'worst of the worst' prisoners in long-term solitary confinement, under conditions of extreme sensory deprivation." It's the only super-max prison in California and notorious for its Solitary Housing Unit, or SHU, which largely houses inmates in isolation and has been the focus of inmate hunger strikes and lawsuits. When it was first opened, 40 percent of the inmates housed there were doing life sentences. Currently, the CDCR website states that half of the current inmates are housed in maximum security general population and the other half are in the SHU. In a 2012 investigation for Mother Jones, journalist Shane Bauer found that "in the Pelican Bay SHU, 94 percent of prisoners are celled alone; overcrowding has forced the prison to double up the rest."

Nguyen entered Pelican Bay around this time and says he felt there was little staff support for inmates, adding that he requested a transfer every year. Then in 2015, College of the Redwoods began implementing a pilot program to bring college courses inside the prison that would allow inmates to work toward a degree.

The program was a direct result of California Senate Bill 1391, which the Legislature passed in 2014, recognizing education in the prison system is proven to reduce recidivism. The bill amended an existing law that required community colleges to keep their classrooms open to the general public, which prevented them from offering courses in closed settings like prison.

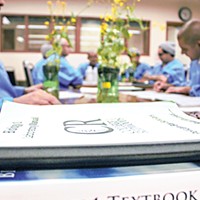

Under the new program, eligible inmates were granted California College Promise Grants, which waived their tuition. The pilot was so successful in its first two years that it grew by 200 percent, tripling the number of students, and, in 2018, CR received a California Community College Chancellor's Office Innovation Award of $1.2 million to fund and expand the program, allowing the college to hire two fully dedicated staff positions — as well as textbooks, calculators and school supplies. The CDCR also provides a full-time coordinator to support the program and additional correctional officer shifts to accommodate expanded course offerings.

What sets the Pelican Bay Scholars Program aside from other college programs in California prisons is that every single professor is a paid instructor of CR and the coursework is designed to work toward an ADT degree. Other prisons in California, like San Quentin, have college professors teaching courses but they aren't all dedicated employees and the coursework isn't necessarily transferable.

Nguyen was one of a handful of students to enroll in the first pilot class and remembers the surreal feeling of sitting down in a classroom.

"At 5 o'clock, we never heard about being let out of our cell except for maybe dayroom or a phone call here and there," he says. "Because this was a pilot program, this had never been done before here. It was a night program and they were really cautious about letting people out after a certain time."

Nguyen says prison administrators told him and the other students that they were setting the precedent for the future of the program and warned that if it "causes too many waves," they would shut it down. Nguyen says he was on his best behavior. He remembers the increased security presence of the first class, but says inmates were generally unbothered by it, grateful to be out of their cells and getting a chance at a college education.

The program's popularity has spread. Eagles says there are currently 300 students enrolled in 28 class offerings taught by 14 instructors, with another 250 students on a waitlist.

Eagles is the backbone of the program. She is at the prison daily, perpetually running back and forth between CR's Del Norte campus and the prison's campus, making sure students have all the necessary supplies, printing research papers and whatever else they need. She stops in on classes throughout the day, checking on students and professors. When she walks down the hallways, the guards know her by name and students reach out to her respectfully as "Ms. Eagles" and talk to her about how things are going. Each of the students the Journal interviewed for this story pointed to Eagles as the reason the program runs smoothly. She listens to them and advocates on their behalf. If they want more classes or professors, she puts in the time and energy to make it happen.

She also works to connect students being released from custody with resources to continue their education, like Project Rebound and Underground Scholars, programs that work to build a "prison-to-school pipeline" by helping students apply and enroll in colleges and succeed once they get there.

"If you don't feel comfortable on a campus it's hard to be successful there," Eagles says. "We help with filling a connection with this campus that will build those confidences."

Working alongside Eagles from within Pelican Bay is Robert Wilson, the prison's rehabilitation program coordinator — a position created solely for the program. Wilson is the point person for inmates looking to enroll in the program. He checks their educational backgrounds to make sure they meet the qualifications and, if they do, puts them on the waitlist and works with Eagles to find them a spot.

"They love it — absolutely love it — and they are really enjoying the ability to take these classes and move toward getting a degree," Wilson says. "It's extremely positive. They're really appreciative and respectful. They know this is an incredible opportunity and the vast majority of them are really making good use of it."

He says the students are highly motivated because they recognize they missed their opportunity at education on the streets and are serious about not wasting a second chance. According to the Prison Policy Initiative, there are more than 2.2 million people in American prisons at any given time and nearly twice as many on parole, probation or some sort of court supervision. Wilson says inmates today are going to be people's neighbors tomorrow and we've got to extend the opportunity for people to change and have access to the tools to be successful in order to break the cycle of incarceration.

"If there's hope, it's through rehabilitation — it's the last initial of CDCR," Wilson says. "I think it's really critical that these sorts of programs continue to grow and, statistically, you're much more likely not to come back to prison if you have a G.E.D and obviously an associates. Truly, we have to ... give people opportunities if we are to give them a chance to change."

Born in Massachusetts, Nguyen's parents fled Vietnam during the war on a boat adrift at sea and were rescued by the Thai Navy. A family member in the United States sponsored them in 1980 and Nguyen was born a short time after. According to Nguyen, "the fates had something else in store for me" and it was written in the stars he would be born in the United States.

Eventually, the Nguyens moved to Long Beach and, after saving enough money, settled in Simi Valley, where Nguyen was raised in a big family, which is something he holds close to his heart. His parents, brother, sister, three uncles, an aunt and grandmother all lived in the same house. He only spoke Vietnamese during his childhood because he was surrounded by first-generation immigrants, which made it difficult when he eventually started school.

"I remember my first day of kindergarten, I didn't know a lick of English and ended up getting into a fight," Nguyen says. "Where I grew up, there wasn't many Asians — only one other family in our neighborhood. I was the only Asian in my class up until middle school, so I ended up getting into a lot of fights because people would try to bully me."

School for Nguyen became a place to be victimized, harassed and ostracized. As he advanced in school, he says he became "fretful and easily overwhelmed by anxiety," which he says contributed to his family relationships beginning to crumble. He eventually started to seek refuge elsewhere, dropped out of high school, found a new family with a street gang and started committing crimes. His younger sister, Diane Nguyen, says her brother was in a bad rut.

"He wasn't very good at expressing his feelings with us," Diane Nguyen says. "When he abandoned family, that's when he came here (prison)."

Today, she says. her brother is more open. They exchange weekly letters and when Diane Nguyen lived in Morro Bay, she would take the 583-mile trek to visit Nguyen in prison once a month because "that's what family does."

The two have always been close and Diane Nguyen says when her brother was sent to prison it was important to her that he knew his family was still there for support.

"Everyone makes mistakes but I don't like calling them mistakes, though," she says. "They're just opportunities to learn and grow."

And Diane Nguyen says she has witnessed a lot of growth in her brother since he started college. She says his compassion for others motivates and inspires her to be the best person she can be, adding that he's always been hardworking and put people before himself.

Nguyen's behavior was so good in prison, in fact, that it almost kept him from graduating. At the beginning of his final semester, he was supposed to be transferred to a lower level security yard, which would have changed his schedule and made it impossible to take the necessary courses to graduate. But he asked to stay at a higher level security yard so he could finish school and Eagles campaigned for him.

"From the beginning, David has shown a great deal of commitment and passion for every project and endeavor he is involved in," Eagles says. "He has a way of engaging that is empowering and encouraging to those around him. He is the first to give kudos and embraces a constructive attitude no matter the circumstances, which are qualities I really respect about him. Essentially for David, every occasion is a we-can-do-this opportunity. The program has greatly benefited from his influence as an active ongoing contributor."

Nguyen speaks just as strongly about what the program has done for him. When he arrived at Pelican Bay and there were no opportunities, he says he passed his time daydreaming and sulking around in negative space. But today he radiates positivity — an attitude that others say becomes contagious in the classroom.

"I've been incarcerated for over 14 years, so I've witnessed when there was no type of programming and the culture was locked down," he says. "It's crazy to be able to do something like [programming] in such a secured environment. I feel like it's a blessing."

If Nguyen has become a shining star of CR's program, some say he is also emblematic of the greater changes the college has brought to the prison.

Wilson says he has seen a transformation within the prison walls over the last few years, and Nguyen and his peers say having the college inside is helping break down racial and gang segregation.

They say the college, coupled with a Prisoners Embracing Anti-hostility Cultural Evolution (PEACE) group, is changing the culture around Pelican Bay. The PEACE group started in 2016 when inmates, some of whom had spent decades in the SHU, collaborated to find ways to keep hostility between races and gangs at a minimum.

After hunger strikes in 2011 and 2013, the Center for Constitutional Rights won a lawsuit against Pelican Bay that forced the state of California to end its policy of holding some prisoners in isolation indefinitely. Before the lawsuit, some inmates spent decades in SHU. Today half of the building that contained the SHU has been knocked down and re-purposed for a lower-custody, level 2 housing unit in which a marine mammal biology class is now taught.

"If you Google everything on Pelican Bay, that's the old stuff," Nguyen says. "Yes, there's still isolated housing and it's still prison and there's still bad apples around, but there's more people level headed walking the yard now than there was in the past. There hasn't been a huge racial riot for the longest time on this yard and that just goes to show."

While there was a riot on the maximum security yard in 2017 that sent eight guards and five inmates to the hospital, things have calmed considerably in recent years, Nguyen says.

"There are some incidents, and there is still a lot of stuff that goes on, but it's not what it used to be," he says.

Nguyen credited the entry-level class taught by Johnson as another factor in helping to break down racial barriers at the prison, as all students must take it before moving on to other courses. Johnson says there's a lot of opportunity for people to share deep experiences, as well as engage in cultural exchange conversations, in the course.

Johnson, a soft-spoken woman with deep blue eyes in her late 40s, says that at first she was unsure whether her students would buy in and participate. That turned out not to be a problem.

"Over the years, I can say there hasn't been one time I asked them to do something in class that they weren't willing to do," she says. "They were very open to do that and they benefited a lot from that kind of an activity and I was amazed."

Johnson admits she was a fish out of water walking into Pelican Bay but she was transparent with her students and they opened up to her. Many students, including Nguyen, pointed to her as a reason they stuck with the program. For her part, Johnson says she remembers Nguyen as inspiring, kind and very supportive of other students.

Fellow student and best friend to Nguyen, Kunlyna Tauch, agrees, saying Nguyen is the reason he enrolled in college.

Nguyen asked Tauch if he was interested in starting school with him but Tauch says he was too busy gang banging to commit. Finally, Nguyen convinced Tauch to sit in on Johnson's class and he came around.

"It all started when David signed me up for Buddhist services," Tauch says. "He was like, 'You need to meditate.' Now I'm the Buddhist peer minister, but it started with that and it kind of linked up with education because it was next door."

Tauch, who first met Nguyen at High Desert Prison, where a guard told him, 'We're going to send you where we send all the guys that fuck up,' before he was transferred to Pelican Bay, is now in line to graduate by next year.

"Man, I'm really glad I met the dude," Tauch says of Nguyen. "I came up here (Pelican Bay) and was doing the same thing and he came and tried to stop it. He was already in his transformation and he was just more soft-toned and I didn't like that, but then I became more receptive. He invited me to his groups and I got closer."

The reason for Tauch's hesitancy was because programs like CR's used to have negative connotations. Nguyen says if inmates did anything productive they were dubbed "programmers" by other inmates, which was a derogatory word for somebody who wasn't with the prison culture. Now, he says, inmates are encouraging each other to enroll in programs and people are actually excited to say, "I'm a programmer, I'm in school, I'm a scholar at CR."

Nguyen admits he's in prison because he needed to be but says he doesn't want to be remembered for the worst things he's done. He says he's been rehabilitated at Pelican Bay, as have the guys he surrounds himself with, and says he almost can't believe the differences he's witnessed there. Today he says everyone on his yard plays basketball together, whereas before everyone self-segregated along racial lines to the point that if a basketball rolled over to another race's area, you couldn't just go over and get it. And in contrast to the derogatory "programmers" comments that kept people like Tauch from enrolling, Nguyen says seeing inmates walking around the yard carrying books and helping each other with school assignments is common.

"We are trying to promote positivity and change," he says proudly. "We want to try to erase all those barriers, slowly we're chipping away at it and it takes time. Because CR is here, people are actually talking about school all the time, we are calling ourselves students now, we are changing our mindset of who we are."

On June 20, 2019, the Pelican Bay Scholars Program held its first graduation ceremony. CR President Keith Snow-Flamer, Eagles, Wilson, professors and faculty were all dressed in caps and gowns to present the very first two graduates their degrees. Nguyen and Larry Vickers (the second graduate) were dressed in red gowns and once they earned their Associates Degrees for Transfer of Liberal Arts: Behavioral and Social Sciences, they moved their tassels from right to left on their mortar board hats, an age-old acknowledgement of what they had accomplished.

Nguyen gave a speech that echoed the words of Martin Luther King Jr.'s famous "I Have A Dream" address and the crowd of students gave an arena-sized ovation. Afterward, those in attendance celebrated with pizza and cupcakes and talked as if they'd just witnessed a miracle.

Traveling from Southern California, Nguyen's father Hung Nguyen, younger sister Diane Nguyen and uncle Howard Nguyen, were in attendance to show their support and struggled to hold back tears.

Before the ceremony, a Pelican Bay Prison employee approached Nguyen's family and told them Nguyen was something special and people like him rarely come around. The employee rested his hand on Hung Nguyen's shoulder and said, "It has been an honor to work alongside your son."

Asked a short time later about his son graduating, Nguyen's father says, "Anything is possible. Nothing is impossible."

In his son's eyes, it's just the beginning.

"In regards to all the things that I have learned along the way from my classes, I will take it and somehow, someway use it to give back to my community," David Nguyen says with an eye toward his parole suitability hearing in 2021. "I know I want to work as a proponent of criminal justice reform but, ultimately, I just want to serve the community."

T.William Wallin is a senior at Humboldt State University majoring in journalism and minoring in Eastern religious studies. He is also a poet and freelance reporter.

Speaking of...

more from the author

-

Artists Inside

Humboldt County is set to pilot a life-changing arts program. Officials hope it will change the jail, too.

- Jan 9, 2020

-

Hot Sauce is the Right Sauce

Exploring local varieties one bottle at a time

- Dec 12, 2019

-

Charmaine Lawson Holds 31-month Vigil for Her Son, Hopes Documentary Will Bring Outside Attention to Unsolved Case

- Nov 16, 2019

- More »

Latest in News

Readers also liked…

-

Through Mark Larson's Lens

A local photographer's favorite images of 2022 in Humboldt

- Jan 5, 2023

-

'To Celebrate Our Sovereignty'

Yurok Tribe to host gathering honoring 'ultimate river warrior' on the anniversary of the U.S. Supreme Court ruling that changed everything

- Jun 8, 2023