The Death of Jeannie Newstrom

Was it elder abuse, neglect or a failure of the system?

By Linda Stansberry [email protected] @lcstansberry[

{

"name": "Top Stories Video Pair",

"insertPoint": "7",

"component": "17087298",

"parentWrapperClass": "fdn-ads-inline-content-block",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

}

]

Before you read the details of Jeannie Newstrom's death or the painful, gruesome and — if the allegations are to be believed — entirely preventable indignities that led up to it, there are some things you should know about her life.

"She was a great cook," says her son Sherman Newstrom. "She made jams and jellies, tuna fish stuff. She canned her own everything. I wish I had gotten her recipes."

Newstrom was born Jeannie Sefried on Sept. 11, 1929. She moved from North Dakota to Arcata just after World War II, becoming a teenage bride to Sherman Newstrom Sr. in 1947. They had three children together: Sherman, Steven and Sharon. Along with working as a butcher and meat cutter in local grocery stores, she was a gardener, cook and grandmother.

"She was very crafty," says Sharon Newstrom Crossland, her daughter. "It skipped a generation with me. And she loved to dance, all kinds of dancing."

Newstrom died in hospice care at the age of 83. According to the California Department of Justice, she spent the last few weeks of her life in constant pain, swaddled in soiled adult diapers, her skin sloughing from her bones, a gangrenous toe infecting her blood. It was not a fate that hardworking Jeannie Newstrom, who was suffering dementia, or her adult children, who thought she was in good hands, could ever have anticipated.

Good narrative demands a crime story with a beautiful victim, an obvious villain and the mechanisms in place for swift justice. But in real life, cases like Jeannie Newstrom's are the rule rather than the exception. Unable to speak, unable to move, long departed from reality and expected to die at any time, Newstrom fell through every crack there is in the system we have set up to protect society's most vulnerable citizens. Her fractured family was unable to care for her or supervise her care. The care home where she spent her final years suffered an unanticipated disruption, and its clients allegedly suffered the consequences. The agency responsible for making sure the care home was doing its job didn't catch the horrific neglect that allegedly led up to her death. Apparently, neither did the public guardian assigned to do what her family could not. And the parties allegedly responsible for her neglect are still awaiting trial three years later.

Crossland says that although dementia softened her a lot, her mother was not an angel: The siblings had tough childhoods, difficult relationships with their mother and with one another.

"I don't want people to think of her as a victim," Crossland says. "But nobody on this earth deserves to be treated that way. Nobody should have to go through that."

"My mom told me that I'd better not put her in a nursing home or she'd haunt me," Crossland continues. "And, by God, she was ornery enough to do it."

But Crossland, who was also caring for her invalid husband, became overwhelmed. Jeannie Newstrom began exhibiting early symptoms of dementia in the mid-1990s, and was being cared for by her boyfriend, Harold Dockter, until his death in 2008. Crossland did bring her mother into the home for a while, but a rift between the siblings led to their mother being put under public guardianship, and then into skilled care. There are some inconsistencies between stories about how involved the family was with Jeannie Newstrom's care; unfortunately, the Public Guardian's Office cannot comment on their wards, even to confirm whether or not Newstrom was under conservatorship. What we do know is that, according to court documents, Crossland and her brothers had a protracted battle over who would care for their mother in 2009, with both sides alleging elder abuse, and that on Nov. 20, 2009, Newstrom went under conservatorship, her assets and fate becoming the responsibility of the county of Humboldt. In June of 2010, Newstrom entered Nina's Care Home, a small, six-bed residential care facility in Cutten.

Crossland and her brother say their mother seemed happy at Nina's. Sherman Newstrom said it seemed clean and that his mom "always put on a smile for him." Jeannie Newstrom was largely in good spirits, besides periodically asking where her beloved Harold was, only to be reminded that he had passed away.

There were a few things that were off, things that Crossland either couldn't quite put her finger on or wasn't savvy enough to know were problems.

"You couldn't get around to see how clean it was," Crossland says of Nina's. "There would be a smell in there. After I got her in there, they took her underwear away from her and put on a diaper and told her to go in that."

Sherman Newstrom says he was pretty "hands off" about his mother's care, visiting her periodically but leaving major decisions to his sister. A care provider himself, there were a few things he thought were odd, but he put it down to a difference in practices.

"They wouldn't let us stay in the room when they were changing her," he says. "I thought that was weird, but everybody has their rules."

There might have been a practical reason Nina's staff didn't let Newstrom's family get a good look at her. Crossland says that her mother — once a large woman — rapidly lost weight after going into care and that the food was "just crap." Crossland says staff refused to tell her what they were feeding her mother or keep her informed about her care. A medical report for Newstrom dated May 18, 2011, lists her existing health problems as Alzheimers, hypothyroidism, rheumatoid arthritis and anemia. She is described as incontinent and disoriented. At the top of the page is a note: "Call [care home] before you visit. Patient is conserved, speak to public guardian with concerns, not patient's daughter." Newstrom's doctor Hal Grotke declined to comment for this story, but on the date of this exam he gave her less than six months to live. From Crossland's perspective, her mother seemed to be OK, and the cost of her stay, around $4,000 a month, was what the estate could afford. Her weight was declining, but Crossland put some of this down to age. Jeannie Newstrom would surpass the doctor's expectations by a year and a half. But by the time she left Nina's in 2013, according to Crossland, she looked "like a cancer patient, like a carcass."

In its annual inspection reports conducted between 2009 and 2012, the California Department of Social Services' Community Care Licensing Division reported few problems with Nina's. In 2009, it reported that residents said they were "happy with the services." Subsequent reports were uneventful. The first hints that something was amiss came in April of 2012, when an investigation found that a resident had been hospitalized multiple times for bedsores. Also known as pressure sores or dermal ulcers, bedsores are a persistent health problem in elder care facilities. If patients cannot adjust themselves in bed or in their chairs to relieve pressure, staff must readjust them, usually every two hours, to prevent sores from forming. Untreated bedsores can become infected and cause deep wounds. The investigation uncovered that a physician's report with a plan of care was also missing from the patient's file. As is standard, the facility stated that it would correct these deficiencies.

On July 26, 2012, Community Care Licensing visited again, this time to investigate allegations that staff at Nina's did not call 911 in a timely manner prior to a resident's death. Although the details on the report are sparse, it appears a resident suffered a medical emergency and staff called the next-of-kin rather than medical personnel. This is not in line with state recommended guidelines for this type of care. In response, the administrator agreed to hold a staff training.

The repercussions to Nina's for the incidents in April and July of 2012 may seem insufficient; in fact they are standard. A complaint will be made by a family member, guardian or whistleblower. The state will come investigate (it also conducts yearly audits). Sometimes there will be proof of misdeeds — doctor's reports, photographs — but investigators often rely on the administrator of a facility to provide documentation that proves or disproves an allegation. When investigating complaints, a CCL licensing agent might speak to family members, staff, residents, law enforcement, social workers or doctors. In some cases, a care facility may be asked to pay a fine.

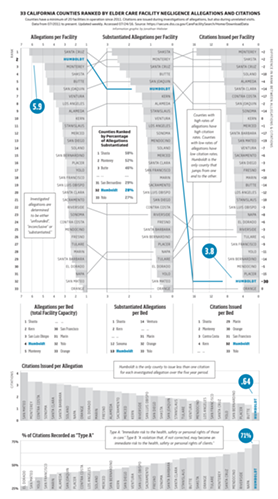

The Journal found that, based on information compiled from the California Department of Social Services' website, there is a stark difference between how many allegations are investigated for residential care facilities in Humboldt County and how many actually result in citations. California has 33 counties with 20 or more residential care facilities that have operated in the last 5 years. Of those, Humboldt had the second highest rate of allegations per facility filed with the department over the last five years, and the sixth highest rate of allegations that were eventually substantiated through an investigation. But, during the same period, Humboldt County ranked 32nd in that group for rate of citations issued. Of the meager number of citations issued, most are punitive "type A" citations, meaning there is "immediate risk to the health, safety or personal rights" of residents, indicating that when allegations are substantiated here, they tend to be serious. In fact, there have been 2.5 times more serious "type A" citations than preventative "type B" citations issued in Humboldt County over the last five years, the largest disparity in any of the 33 counties.

Michael Weston, deputy director of public affairs and outreach programs with the California Department of Social Services, attributes this gap between complaints and citations to a very proactive advocacy base in Humboldt County, that might be more engaged in calling his department. “We do know that Humboldt is a very engaged community in regards to the assisted living facilities, they do engage us in filing complaints. When we do find an issue we investigate it thoroughly,” said Weston.

Community Care Licensing, which inspects not only residential care but adoptive and foster homes, adult day care and other facilities, is essentially a "toothless" organization, according to Suzi Fregeau, manager of the long-term care ombudsman program at the Area 1 Agency on Aging. As an example, Fregeau cites another residential care facility in Eureka, Chamberlain's Care Home, which CCL visited 20 times between January and May 2014 to investigate allegations that its owner, Gina Chamberlain, had locked one client in a bedroom and stolen hydrocodone, money, a Rolex watch and a car from two others.

Fregeau says she became frustrated with the pace of CCL's investigation. Complaints about theft were filed as far back as August of 2013, she alleges. She provided CCL with pictures of the allegedly stolen car, which she said she witnessed Chamberlain driving.

"They did nothing," she says. Chamberlain's continued to take in new patients. A report filed by CCL on April 9 confirmed all of the allegations, but the facility was not shut down until May 5, 2014. "Somewhere along the line, someone should have said something," Fregeau says. "I personally hold them responsible for a minimum of August on."

Weston disputes this interpretation of events.

"If you look at the data, half of the visits made [to Humboldt County in 2014] were coming in to that facility. That's the department elevating and escalating oversight of the facility," he said. "When you do a license revocation, the burden of proof is on the department."

If investigating allegations into a facility takes a long time, bringing bad actors to justice can take even longer. The Chamberlain case did not see its day in court until March 2016, when Gina Chamberlain was convicted of her crimes. But Chamberlain, who failed to appear at a July administrative hearing, has not yet had her license formally revoked (it is currently suspended). In an email, Weston said the state is moving forward with this legal action, which will also mean a "lifetime exclusion from any facility licensed by the Department." It is unclear when this will be completed.

In the case of Jeannie Newstrom, Weston stresses that Community Care Licensing agents aren't doctors.

"[Licensing Program Analysts], when they're in a facility, they're not there to assess a resident, not there to do medical evaluations," says Weston. "They're not medical professionals. They're there to ensure there is care and supervision of residents."

The turning point for Nina's Care Home came on May 1, 2013, when its owner, Nina Winogradov, was struck and killed by a vehicle while walking her dog. Winogradov, the long-time partner of local television personality and newspaper columnist Dave Silverbrand, opened the care home in 1989. Upon her death, the estate passed to her children, who decided to shut the facility down. It was placed under the administrative care of Winogradov's friend, Mia Hyongcha Bressler. The estate also hired a local registered nurse, William Clawson, to assist in transferring the patients to a new facility.

Clawson has an obscure role in the local health care industry. His company, Quest for Excellence, bills itself as offering "personal and professional advancement productions." The language on Quest for Excellence's website is an exercise in opacity. Its parent company, Wm Clawson Enterprises, Inc., is a "California religious non-profit corporation."

Quest for Excellence is "dedicated to the development, production, support, and continuous improvement of services and products which serve to promote personal, spiritual and professional excellence," according to its website. After examining the services advertised, this appears to translate to providing continuing education for health care providers such as those in elder care or nursing. Many professionals must complete a certain number of continuing education credits per year to retain their licenses. Quest for Excellence is one of only three agencies on the North Coast authorized by the state to provide such classes. Among its offerings are seminars on adult residential facility certification ($525), sexual harassment prevention ($45) and a Mexican Riviera Cruise Continuum of Care Conference (price upon request).

In his biography on the organization's website, Clawson's name is trailed by a long list of credentials: PhD, BSN, DipN, RN, PHN, CLNC. The DipN (Diploma in Nursing), RN (Registered Nurse) and BSN (Bachelor's of Science in Nursing) are pretty straightforward. The CLNC (Certified Legal Nurse Consultant) allows Clawson to offer consultation to attorneys on medical issues. Clawson touts his graduation from the "prestigious" Vickie Milazzo Institute, but according to a consumer complaints board, the Milazzo Institute's certification is largely decorative, unnecessary to become a CLNC. Ironically, CLNCs are often called to testify in courts as experts. Clawson does not say where he got his PhD; it's in Religious Studies, obtained from the Universal Life Church of Modesto in February 1996, a month after he became an ordained minister there.

It is unclear how much Newstrom had already deteriorated prior to coming under the care of Clawson in May of 2013. Fregeau alleges that Community Care Licensing had noted issues with bedsores; she may in fact be the patient mentioned in its April 2012 report. It is also unclear how much oversight the facility's administrator, Winogradov, had over the care home prior to her death. She did not sign the reports from Community Care Licensing in 2012 and 2013; Bressler, who according to Fregeau, was not qualified to be an administrator, did. The Journal reached out to the attorneys for both Clawson (Marion Miller) and Bressler (Neil Sanders), but they did not return our calls. We were also unable to reach Silverbrand or Winogradov's children. Bressler was the principal caretaker at the facility after Winogradov's death, and was responsible for feeding, bathing and oversight of the patients. But Clawson, with his long list of qualifications, was responsible for assessing the five remaining patients and making sure they transitioned smoothly into other facilities.

Representatives from Community Care Licensing visited the facility on May 9 and 21. On May 11, 2013, Clawson signed off on the paperwork saying that Newstrom was fit to transfer.

The allegations against Clawson, which are based on interviews conducted by Community Care Licensing and detailed in a 10-page accusation by the Board of Nursing calling for the revocation of his license, include "gross negligence" and "incompetence." According to the report, Clawson did not physically handle Newstrom, but stood by while Bressler did the examination. He also declined to examine Newstrom in the 13 days that followed. The Board of Nursing said he "took the position that it was not his job to check on any patients after the initial assessment."

Crossland, who stopped by the home periodically during this time to check on her mother and observed she was looking gaunt, has a low opinion of Clawson.

"He barefaced lied to me, right to my face," she says. "I had to go there and I asked him, point blank, if she was OK to be moved. He said she would be fine."

Crossland was also troubled that her mother was wrapped in clothing from head to toe, with long pants and a sweater. But it didn't occur to her that someone might be trying to cover something up. Newstrom had lost most of her ability to speak by then. She was uncomfortable, only able to move a little bit in the bed.

Newstrom had been taken to a podiatrist a couple of weeks earlier, on April 29, and diagnosed with gangrene. Her feet were wrapped from her ankle to her toes with instructions that the dressings be changed every day. According to the accusations, the dressings had not been changed when Clawson examined her; they were not changed for almost a month. The Community Care Licensing agents apparently did not notice the smell of rotting flesh during their May 9 visit, but their report says they met with Bressler to "document the status of the remaining residents in care." There were then five residents at the house.

According to the report from CCL's May 9 visit, agents met with Bressler and spoke over the phone with Winogradov's son to confirm the closure plan for the facility. Physically checking as to whether Newstrom was fit to be transferred was outside the scope of their duties, Weston says.

"It is the responsibility of the care providers to make those determination if the needs of the resident exceeds the care of the facility," says Weston.

"CCL generally requests that a doctor perform the resident evaluations," reads the accusation, "... But if a facility cannot obtain an appraisal from a doctor, CCL will send their own RN consultant to assess the residents. ... Given that Respondent, an RN, had performed the patient assessments, CCL accepted them."

According to the Board of Nursing's accusations, during the May 11 examination, Bressler noted that Newstrom was emaciated and had a rash on her rear end. Her groin and peri-rectal area were also inflamed. The accusation says Newstrom's public guardian was not notified. Clawson asked Bressler to sign off on the assessment but she refused. In the intervening days, the Board of Nursing says that Bressler told Clawson that Newstrom had skin tears on her arm and behind her knee, but he did not check on her, despite visiting the facility between six and nine times.

On May 23, staff from Frye's Care Home arrived to help transfer Newstrom to her new facility. Crossland, who was also there, suggested that they dress her mother in jeans, but Bressler responded, "No, she's all glued up." What that meant would become apparent once she arrived at Frye's.

According to the Board of Nursing's report, the smell of urine and feces followed Newstrom, who "yelled out in pain," during the move. Once at Frye's, the staff prepared her for a shower and body check. As Newstrom yelled "Oh Lord, help me," and "Ow, it hurts," they carefully removed her clothes. The report states that Newstrom was covered in bedsores, 12 in all, from her chest down to her toes. Some of her clothes and gauze were stuck to the wounds, and the staff had to use sterile water to loosen and remove them. An open wound "at least four inches in length," had formed behind one knee, so deep that staff saw the tendons of her leg. Newstrom's gangrenous toe was now black, according to the report. She was wearing multiple diapers and, under those, four pads soaked in feces and urine. Feces coated her lower torso, dried to her skin. The staff called 911. Hardworking Jeannie Newstrom, who loved to dance, went to the hospital.

She died in hospice care 16 days later, on June 8, 2013.

Now dead for more than three years, Jeannie Newstrom continues to fall through the cracks. In 2013, the district attorney, Paul Gallegos, declined to press charges against Clawson or Bressler. His successor, Maggie Fleming, did not know why. Community Care Licensing sent its report to the Board of Nursing, where it languished until 2015. The California State Attorney General is now prosecuting the criminal case, but the trial has been delayed three times already and is now scheduled for later this month. Clawson, who is charged with one count of elder abuse, is still a registered nurse. He is still an associate member of the North Coast Association of Residential Care Administrators. He is still charging for courses on how to care for the elderly. His alleged crime is punishable a maximum of four years in state prison. Bressler faces additional allegations that she caused great bodily harm, which may add another 12 years if she's convicted.

Joyia Emard, public information officer with the California Board of Nursing, could not speak as to why Clawson and Bressler were not charged with elder abuse back in 2013. The Board of Nursing does not have jurisdiction over criminal charges, but it can revoke Clawson's license after a proper hearing.

"The investigations can take quite a while," Emard says. "They need all kinds of documentation: autopsy reports, interviews. There's a lot involved to this whole investigative process, especially if people aren't being cooperative."

She adds that it's not unusual for cases to take a long time if licensees have hired a lawyer; Clawson has. And these cases are a rather low priority for an overburdened court system.

Fregeau's diagnosis is succinct.

"The system failed Mrs. Newstrom," she says. She adds that Clawson called her on May 24, 2013, to file an elder abuse report, ostensibly against Bressler. By then, Fregeau had already heard the facts and, optimistically, perhaps, thought justice would be forthcoming.

Comments (9)

Showing 1-9 of 9

more from the author

-

Lobster Girl Finds the Beat

- Nov 9, 2023

-

Tales from the CryptTok

- Oct 26, 2023

- More »

Latest in News

Readers also liked…

-

Through Mark Larson's Lens

A local photographer's favorite images of 2022 in Humboldt

- Jan 5, 2023

-

'To Celebrate Our Sovereignty'

Yurok Tribe to host gathering honoring 'ultimate river warrior' on the anniversary of the U.S. Supreme Court ruling that changed everything

- Jun 8, 2023