The Atomic Priesthood, Giant Rutabagas and What's Next for Humboldt's Decommissioned Nuke Plant

By J.A. Savage[

{

"name": "Top Stories Video Pair",

"insertPoint": "7",

"component": "17087298",

"parentWrapperClass": "fdn-ads-inline-content-block",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

}

]

Humboldt's nuclear power plant is strictly prohibited by federal authorities (Nov. 4), celebration of the final decommissioning of the reactor site at King Salmon Nov. 18 was cut short. After environmentalists put down their sparkling beverages, they suddenly realized that with decommissioning done and the feds basically out of the picture, there's no reliable entity to take over the task of ensuring public health and environmental safety from radioactive waste.

Never fear, notes the Nuclear Regulatory Commission. The incredible design of the containers for high-level radioactive wastes stored on a bluff at Buhne Point won't cause us local humans, our ocean or our critters to glow in the dark. The agency has ruled out deleterious effects of tsunamis, earthquakes and sea level rise on the containers holding the radioactive waste. For now. But, it says, ask again in a few decades.

Unfortunately, the high-level waste at the site is expected to be toxic for more than 100,000 years, while the casks holding in the radioactivity at the site have a "design basis" to last 60 years.

Radioactive "dose rates" at the Humboldt nuclear storage site will be "as low as reasonably achievable" and "decreasing over time due to the decay of the fuel sources stored inside," according to a November 2021 federal nuclear commission report. "There is no credible event that could cause an increase in dose rate from" the facility. "Low," in the case of regulator-speak, means "making every reasonable effort to maintain exposures to ionizing radiation as far below the dose limits as practical."

Why be concerned about Humboldt's nuclear waste? Because it's one of the most toxic substances on earth. It can be breathed in, swallowed or assimilated just by exposing some skin. Scientists report that once inside the body, it emits alpha, beta and gamma particles. Those in turn, ionize molecules and start breaking up chemical bonds, damaging a body's cells. It wreaks havoc, particularly, on DNA molecules.

Federal regulators exude confidence that no radiation will leak out, even with the stormy Humboldt Bay shoreline, which sees constant "small craft advisories," sea-level rise and harsh weather. The storage facility is deemed so impervious that regulators are only requiring the area to be monitored for radiation for another six months, saying there's "no need" for continued monitoring. "There's no accident scenario," that would lead to a radiation release, said David McIntyre, a spokesperson for the Nuclear Regulatory Commission.

For instance, the worst-case tsunami at high tide considered by regulators would stop 1 foot below the top of the storage vault holding the canisters of nuclear waste, according to a November 2021 analysis by the Nuclear Regulatory Commission. The vault sits 44 feet above mean high tide. And if the canisters do get dunked, they're "designed to withstand the static pressure forces from submergence in 656 feet of water," according to the November filing, which reviewed a myriad of tests on the devices.

But Jennifer Marlow, an assistant professor in Humboldt State University's Department of Environmental Science and Management, doesn't quite believe those promises. She is "particularly concerned" about tsunamis overtopping the rock seawall along Buhne Point, "rapidly eroding the 115-foot shoreline buffer, inundating the [canisters] with saltwater, cracking the casks and causing radioactive leakage," as she warns on her website www.44feetabovesealevel.

"By 2065, Humboldt Bay is projected to experience 3.3 feet of sea-level rise, which will flood the low areas around the [waste site] during king tides, turning it into an island that will be vulnerable to wave erosion and saltwater intrusion, and difficult to access for waste management and relocation," she writes.

But even if all the federal safety projections are true, the government is only relying on them for the next 40 years, about the time that Marlow fears the site will be swimming. "PG&E had to show that aging wouldn't impact the safety function" of the storage site to get federal approval, according to McIntyre. PG&E is required to be watchful of "aging management" until its current federal license for waste storage expires in 2060. Then, "PG&E will have to take action prior to 2058 (timely renewal requirements) either to apply for an additional license renewal or move the fuel offsite to another storage/disposal facility," he added in an email.

No matter how federal regulators are viewed — whether complicit in hiding the nuclear industry's shameful secrets, or champions keeping the industry from carelessly contaminating entire regions — the courts have forbidden states like California from stepping in to protect us from radioactivity. Instead, state agencies can only nibble around the edges of the issue. The California Public Utilities Commission can make sure some money is set aside for future safety needs. The California Coastal Commission can also require permits to shore up the site if and when it starts slip-sliding into Humboldt Bay.

While the state has appeared more than willing in the past to take on the responsibility for public health and safety of nuclear plants, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in the 1970s that California, and others, had to keep its hands off of anything with radioactivity — keeping the public safe from toxic radiation is solely in federal jurisdiction under the "supremacy clause." In context, it was an era of widespread nuclear power plant development and, at the time, California was looking for ways to halt construction of more nuclear plants along its coast.

It was also a time when the radioactive waste from all the nukes in the nation was all supposed to be gathered up and sent to a forever burial site somewhere in the desert. That never happened. It's unlikely to happen in the future. So putting all the power over health and safety at the federal level means once the Nuclear Regulatory Commission deems decommissioning is done, there appears to be a very little in the way of continued oversight. Federal regulators are also subject to the whims of changing presidents because the commission itself is comprised of political appointments.

Now that the Nuclear Regulatory Commission is only watching the decommissioned Humboldt site from afar, the gravity of that lack of radioactive watchfulness has yet to ripple its way to the few policy makers who could try to mitigate it. When and if the state government decides to address any potential threats from long-term waste storage on the bay, it will have to find creative ways to look out for safety through financing and permitting — the two areas the state is allowed to influence nuclear power. So, while the state's hands are zip-tied as far as keeping us locals safe from radiation, there's just a little wiggle room under the restraints.

The California Public Utilities Commission is one avenue for wiggling into public safety, but it's restricted to making sure PG&E has the money to accomplish cleaning up and meeting safety requirements. Regulators were most anxious to make sure there is enough money to pack up PG&E's more notorious nuke site, Diablo Canyon. Humboldt was, at best, an afterthought, with the commission providing $3.9 million a year for PG&E's continued work at the plant at its Sept. 9 meeting. Humboldt's decommissioning so far has cost ratepayers $1.1 billion.

With the Public Utilities Commission limited to policy covering financial wherewithal, the last established place the public can look for long-term responsibility is yet another commission — the California Coastal Commission. And while that entity can't touch health and safety issues either, it has a backdoor to protect against environmental hazards.

The Coastal Commission's superpower is permits. It's well known to anyone who's attempted to modify an existing home or structure, cut trees or build along Humboldt's coastline that the Coastal Commission can regulate the hell out of the permitting process. And in so doing, it can address at least some safety issues from the structures, erosion and other physical surroundings shoring up the radioactive waste site.

When the Coastal Commission permitted PG&E's nuclear waste storage in 2011, it required the utility to measure the bluff holding up the waste storage casks. "If erosion gets to a certain point, it triggers a return to the commission," Tom Luster, Coastal Commission environmental scientist, said. Specifically, he referred to the decade-old permit conditions for the structure that note if the slope shows "any horizontal or vertical movement of the bluff slope or edge of 2 feet or greater" in five years' time, the utility has to keep a closer eye on it, reporting to the state on the slope's condition annually. If the slope crumbles, like what happened to the bluffs at Big Lagoon, PG&E would have to report immediately to the Coastal Commission and would be expected to fix it. If you haven't walked the county beach at Big Lagoon to witness what can abruptly happen to structures once a bluff decides to crumble, this reporter's personal experience is that one day there's a house on a wide bluff, the next day a house teetering on the edge.

Bluntly, the Coastal Commission appears far more worried than federal regulators about the vulnerability of the waste storage site. The area, noted a commission analysis, "has experienced one of the highest coastal erosion rates documented in the state, [and] is only protected from that erosion by a revetment that has required extensive maintenance in the past, and will only remain safe in the future with continued maintenance and, perhaps, expansion of the coastal armoring."

"If monitoring results for any reporting period indicate slope movement that may require additional measures to

protect the development, [PG&E] shall submit a coastal development permit application," state regulators noted in their 2011 waste storage permit. That's where the Coastal Commission can wave its permit super cape to try to safeguard the public.

But if none of the state and federal commissions can come up with a very long-term policy to keep radioactive waste at the edge of Humboldt Bay bottled up for hundreds of thousands of years, there's also the unprecedented and frightening academic concept of creating a Nuclear Ministry of the Future, the Atomic Priesthood.

The Atomic Priesthood concept originated when "atomic" energy was assimilated into America as a positive force after all the negative publicity from the atom bombs at Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Japan, in World War II. A "religion" could be created around nuclear waste sites so information about their hazards could be passed through generations, no matter the change in language or politics.

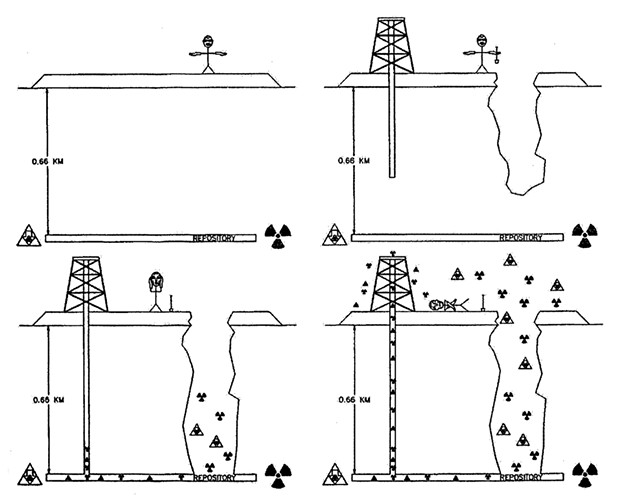

The federal government at Sandia National Laboratories was trying to invent a visual code that humans hundreds of thousands of years in the future would be able to interpret as a warning not to dig up the site. According to its chief advocate, biosemiotician Thomas Sebeok, nuclear waste information would be "passed on into the short-term and long-term future with the supplementary aid of folkloristic devices, in particular a combination of an artificially created and nurtured ritual and legend."

The main component of the Atomic Priesthood would be that "the uninitiated will be steered away from the hazardous site for reasons other than the scientific knowledge of the possibility of radiation and its implications; essentially, the reason would be accumulated superstition to shun a certain area permanently." The concept was feared to be too cult-like by President Ronald Reagan's administration, and thus rejected. But it has retained at least some interest into this century by another federal agency, the U.S. Department of Energy's Waste Isolation Pilot Plant, which buries lightly radioactive debris in the salt mines near Carlsbad, New Mexico.

With or without an Atomic Priesthood, the land that formerly hosted the reactor itself next to Humboldt's waste storage site could be open to the public at some point. The Nuclear Regulatory Commission's suggested use is farming.

What might grow next to a radioactive waste storage site isn't clear. Humboldt's soil is proven to grow giant sinsemilla, acres of quinoa and award-winning rutabagas. Neither PG&E, nor federal regulators could offer an example of what, if any, crops are now grown on other former nuclear power plant sites. But if an Atomic Priest and a giant rutabaga walked into a bar ....

J.A. Savage's (she/her) perfect public utility would be forthright and honest; responsible to its ratepayers and the environment. That, and airborne pigs and unicorns would thrive in her Eureka backyard.

Comments (4)

Showing 1-4 of 4

more from the author

-

44 Feet

The de-facto nuclear waste site on the edge of Humboldt Bay and one group's efforts toward an atomic-ally correct future

- Sep 15, 2022

-

Geopolitics Undermine Energy Authority’s Solar Project

- May 1, 2022

-

Aquafarm Ecology: Energy and Water in, Water and GHG Out, Fish on the Go

- Mar 3, 2022

- More »

Latest in News

Readers also liked…

-

Through Mark Larson's Lens

A local photographer's favorite images of 2022 in Humboldt

- Jan 5, 2023

-

'To Celebrate Our Sovereignty'

Yurok Tribe to host gathering honoring 'ultimate river warrior' on the anniversary of the U.S. Supreme Court ruling that changed everything

- Jun 8, 2023