[

{

"name": "Top Stories Video Pair",

"insertPoint": "7",

"component": "17087298",

"parentWrapperClass": "fdn-ads-inline-content-block",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

}

]

On Jan. 21, a beautifully sunny day, two women from Red Bluff were walking on the beach at Dry Lagoon with their three dogs when a wave swept up and pulled them into the ocean.

Jamie Dickison, 27, and two of the dogs survived. Dickison's spouse, Veronica "Vee" Dickison, 29, and her dachshund, Fyn, did not. Four days later a Humboldt County Sheriff's search and rescue crew found her body on a beach two miles to the south, at Big Lagoon.

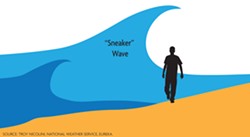

It was the first "sneaker" wave death in Humboldt County this year. And every year, three to five people die after being caught by a suddenly bigger wave and dragged into the cold, chaotic water. These waves often are described interchangeably as "rogue," "sneaker" or "sleeper" waves in news reports. Sometimes the reports note that out-of-town visitors tend not to know the ocean very well. Often they note the ocean's dangerousness on stormy days.

But stormy days, super high waves and inattentive visitors have not, in fact, been common factors in Humboldt County sneaker-wave deaths, says Troy Nicolini with the Eureka office of the National Weather Service, who lately has been sharing with local groups a theory he and his colleagues have developed about when sneaker waves form that they think might help people better avoid them.

Several Redwood National and State Parks personnel who often work on the beaches have had close calls with sneaker waves. And the Dickisons had lived in Humboldt County and spent lots of time at the beach, including surfing.

"Jamie is very ocean-savvy," said Nicolini last Friday at his office on Woodley Island.

Human behavior and weather do seem to play a role, however, said Nicolini -- just not the one we might think. Sneaker-wave deaths, he said, have all happened on sunny, calm days, often during a rising tide -- and in each case the wave that got them was no bigger than eight or 10 feet.

"And the recurring theme of what survivors say is, ‘The wave seemed to come out of nowhere and completely caught us off guard,'" said Nicolini. "‘One minute we were on dry sand, the next minute we were in chest-deep water.'"

The pattern defies the usual notion about "danger" at the ocean. "At 18 feet, for example, we issue a high surf advisory," said Nicolini. "And at 22 feet we issue a high surf warning. Well, nobody for the most part is getting killed when the waves are that big -- with the exception of someone on a jetty or a rock or a cliff, where they tend to get really close to those big waves because they have a false sense of safety."

As for the beach, says Nicolini, people instinctively know to stay far from the shore on stormy days when the waves are obviously huge and crashing. Or they don't go at all. On sunny, calm days, however, not only are more people at the beach, but the weather itself creates a wave-set pattern that produces sneaker waves and also, ironically, induces people into letting their guard down. Nicolini says on such a calm day, people will note quickly where the waves are hitting and assume that's where they'll continue hitting aside from a slow change with the tide. But they might be wrong.

Aside from the tides, created by the moon's gravitational pull, and the occasional tsunamis, waves are born by wind pushing on the water and can come from any distance -- from a thousand miles away, 60 miles, a couple of miles or from a storm right on top of you. Long-distance waves, which increase in height, wavelength and speed as they travel, can outrun shorter, locally produced waves.

"So on a day when lots of different waves exist, you've always got some adding up and some canceling out each other. And what you get is a really homogeneous wave through time," Nicolini said. "Ironically, these waves, they might be kind of big, but they all end up about the same when they hit the beach. Now, imagine a day where all the waves are coming only from far away -- thousands of miles."

This turns out to happen on sunny days -- no local storm, no local waves. These long-distance waves can look like one big wave, Nicolini said. But they are more like brother-sister waves -- nearly identical, but traveling at slightly different speeds. They're recognizable by their long crests -- the width of the wave from left to right as you stare at it from the beach. And because they have traveled far, and lost the push from their original wind, their profile may have smoothed out; from the beach, the ocean might even appear flat.

As they travel, at slightly different speeds, sometimes these near-identical waves are out of synch, and they cancel each other out, making smaller sets of waves. Other times they synchronize, or add up, for awhile, and produce a set of larger waves -- sneaker waves, which, in Humboldt, have been known to sweep as far as160 feet higher up the beach than the smaller set of waves before them.

Ideally, suggests Nicolini, you should watch the ocean for a good 30 minutes before venturing anywhere near it, to see what the sets are doing. But most people won't do that. So, he says, at least be aware of the conditions for sneaker waves. If it's sunny, expect them (and if it's stormy, you already know the waves can be big and dangerous). Look for the long wave crests. If the tide is rising, know that sneaker waves can come in even faster. And if you see that the sand is wet farther up the beach than where the waves are currently breaking, well, that's probably where a large set recently came in. If you have to get near the water, to agate hunt or fish or whatever, have a spotter and wear a life vest, he says.

Nicolini advises against using fear as a tactic to warn people about sneaker waves. Half the population will just stay away from a perfectly nice beach experience, he says. The other half will go devil-may-care into the danger zone thinking their chances of being caught by a "rogue wave" are slim, like being hit by an asteroid.

But sneaker waves aren't rogue waves.

"A rogue wave is actually a well-documented phenomenon," Nicolini said. "It's twice as high as most waves, and it's statistically rare. It might happen once a year."

Sneaker waves, on the other hand, are common -- and even somewhat predictable.

Speaking of Sneaker Waves

-

Sunny Skies for Holiday Week but Sneaker Waves Possible Turkey Day

Nov 21, 2022 -

Halloween Forecast: Light Rain and Sneaker Waves

Oct 30, 2022 -

High Risk of Sneaker Waves on Saturday

Feb 25, 2022 - More »

more from the author

-

From the Journal Archives: When the Waters Rose in 1964

- Dec 26, 2019

-

Bigfoot Gets Real

- Feb 20, 2015

-

Lincoln's Hearse

- Feb 19, 2015

- More »

Latest in News

Readers also liked…

-

Through Mark Larson's Lens

A local photographer's favorite images of 2022 in Humboldt

- Jan 5, 2023

-

'To Celebrate Our Sovereignty'

Yurok Tribe to host gathering honoring 'ultimate river warrior' on the anniversary of the U.S. Supreme Court ruling that changed everything

- Jun 8, 2023