Not Expelled But Not Fully Welcome

Japanese experiences in Humboldt's Chinese exclusion era, from education to terrorism

By Alex Service[

{

"name": "Top Stories Video Pair",

"insertPoint": "7",

"component": "17087298",

"parentWrapperClass": "fdn-ads-inline-content-block",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

}

]

Editor's note: This story includes racist language in quotations from historical newspaper articles.

Humboldt County's Chinese history is notorious. For nearly 70 years, from the mid-1880s to the early 1950s, a keynote of Humboldt's public identity was the (false) assertion the county had successfully expelled all its Chinese or Chinese American residents. During one expulsion event in 1906, a past and future mayor of Eureka declared in a public meeting that Humboldt County was "no place for Chinese." This county's "no-Chinese" status was a source of aggressive and sometimes defensive pride for many in Humboldt, though changing socio-political realities, demographics and perspectives have since rendered it a shameful stain on our history.

Among the multiple complexities within the history of Humboldt's Chinese exclusion era are the anomalous experiences of one particular ethnic group: Japanese immigrants. Classified ads and newspaper articles from the period paint a somewhat disjointed picture, hinting that Japanese residents were accepted here in some capacities until racist tensions inspired an act of terrorism that may have played a part in a 40-year period in which no one of Japanese origin or descent officially lived in Humboldt County.

From early in the exclusion era, one generalized understanding has been that Humboldt was not simply "no place for Chinese" but no place for people of any Asian ethnicity. Among the "potent facts" listed in a circa 1915 guide to Humboldt was the claim that this county had no Chinese or Japanese people within its borders. A 1937 Humboldt Times article was headlined "No Oriental Colonies Have Thrived Here Since 1885."

However, the infamous Section 190 of the city of Eureka's ordinances, which was not officially repealed until 1959, only specifically identified Chinese people in its racial prohibitions, stating among other restrictions that "No Chinese shall ever be employed, either directly or indirectly, on any work of the city." Japanese people were not mentioned, which underscores a source of uncertainty within the county's formidable racist forces during the exclusion era. They faced the question of whether Humboldt's people should see all "Orientals" as being fundamentally alike, or whether they saw meaningful differences that could justify admitting Japanese immigrants into the county.

When Humboldt's Chinese residents were forcibly expelled in 1885 and 1886, few Japanese people had yet made the journey to America. Japanese immigration to the United States began about a generation after Chinese immigration. U. S. Census records show 148 Japanese people (mostly students) in the entire nation in 1880, with 2,039 in 1890 and 24,326 in 1900. In contrast, the Chinese populations in the United States in those three census years were 105,465, 107,488 and 118,746, respectively. The smaller numbers meant that during the height of anti-Chinese persecution in the 1880s and 1890s, Japanese immigrants were viewed as more of a curiosity than a threat or a divisive political issue.

The first Japanese visitors to Humboldt were probably a group of acrobats billed as the Prince Satzuma Royal Japanese Troupe, who performed here in August of 1876. In the late 1860s, the Japanese government ended its prohibition against Japanese citizens traveling abroad. Almost immediately, troupes of acrobats and jugglers became the first groups of Japanese to travel extensively overseas. The Prince Satzuma Troupe performed in Mexico and Arizona before embarking on their California tour, which included performances in Ferndale, Rohnerville, Hydesville and Arcata, as well as several in Eureka. Ticket prices ranged from 25 to 75 cents. The Humboldt Standard praised the troupe and advised, "Every man should go and take his wife and sister. If you haven't any of your own, take some other fellow's. But don't fail to go and see them."

Historical research has not discovered the identities of Humboldt's first Japanese residents, nor whether any Japanese people lived here during the mid-1880s Chinese expulsions. If they did, they were probably students at the Humboldt Seminary conducted by Isabella and Mary Prince, Maine-born sisters with illustrious careers as educators in the United States and Japan.

The 1880 U.S. Census showed the Princes in San Francisco as schoolteachers who also ran a boarding house. One of their boarders was a high-ranking diplomat, the vice-consul of Japan. Probably through this connection, the Prince sisters gained prominence for their work with Japanese students who traveled to the U.S. to continue their education.

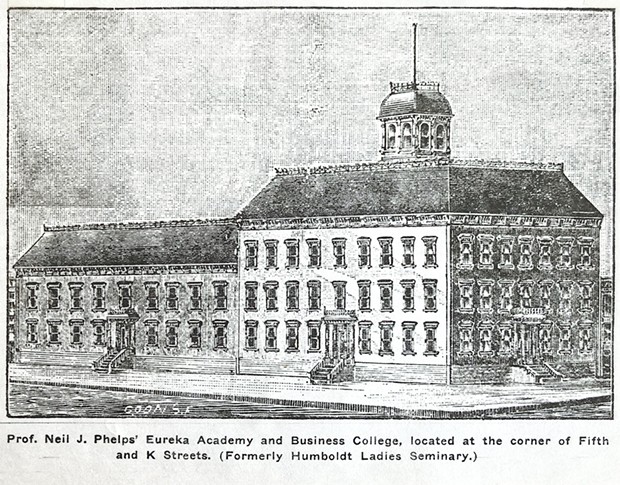

In 1882, Isabella and Mary Prince became head-teachers of the Humboldt Seminary at Eureka's Fifth and K streets (across from today's Humboldt County Courthouse). Although no direct proof has yet been found that they taught Japanese students here, Mary Prince's 1918 obituary states they did. According to the Portland, Maine, Sunday Telegram, "Miss Prince went to Eureka, Cal., where she opened a school called Humboldt Seminary ... Here many Japanese pupils were sent to get American ideas and so successful was Miss Prince in her work that she was finally called to go to Tokio [sic] to teach in a government school."

If any of the Prince sisters' "many Japanese pupils" were indeed studying in Eureka in 1885, during the mob violence and expulsions of the city's more than 300 Chinese residents, one wonders how impressed they could have been with "American ideas."

Mary Prince traveled to Japan in September of 1886 and she and her sister lived in Tokyo for the next quarter-century, running the government-sponsored "American School" for upper-class girls. Shortly after the Princes' departure from Eureka, the Humboldt Seminary re-opened as the Eureka Academy and Business College, under the leadership of professor Neil Phelps.

During Phelps' time at the academy, two Japanese men are known to have studied there. Nishimura Shun is known to us from two articles in The Ferndale Enterprise. On June 15, 1888, the Enterprise listed "Shun Nishimura, Tokio, Japan" as a graduating member of the Academy's Commercial Course. Then on June 29, the Enterprise noted, "Shun Nishimura, a graduate of the Eureka Academy, has taken his departure for Tokyo, Japan, his home."

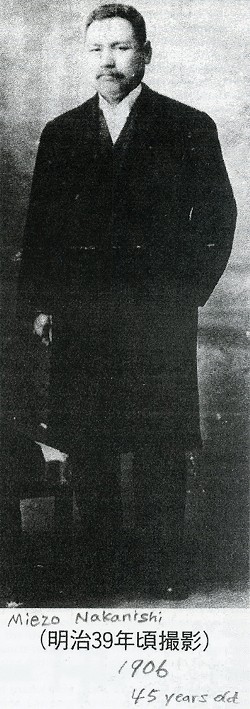

Twenty-seven-year-old Nakanishi Miezou graduated from the academy in May of 1889. The commencement announcement for Nakanishi's class, listing "M. Nackanishi, Japan" among the graduates, is preserved in the collection of the Humboldt County Historical Society. After earning a business degree at Chestnutwood Business College in Santa Cruz, Nakanishi returned to Japan. In 1897 he was the founding business manager of The Japan Times, Japan's first English-language newspaper.

Although our knowledge of them is frustratingly incomplete, it's clear that other Japanese people lived in Humboldt in the late 1880s. Throughout 1887, The Humboldt Times carried classified ads similar to this one from March 22: "Wanted — a situation in a private family to cook and do housework, by a young Japanese." In October of the same year, the Times carried an ad from prospective employers: "Wanted — A Japanese boy, or a girl, to do general housework for a small family. Apply at Dr. Lewitt's residence, corner of Fourth and H streets." One wonders whether the ad that ran Dec. 27, 1887 was placed by Eureka Academy student Nishimura Shun: "An Intelligent Japanese Student desires a situation in some office or store."

A maddeningly limited glimpse of one Japanese community member is found in the June 19, 1888, Times:

Jay Eshigami, a native of Japan, has declared his intention of becoming a citizen of the United States. He is the first Japanese to do so in Humboldt County. The US Supreme Court has declared that the naturalization laws do not apply to Chinese, and that no Chinaman can become a citizen of this country. Whether or not this decision includes Japanese as well, is an open question.

No other information about Jay Eshigami has yet been discovered. There seem to be no records indicating that anyone of that name became a naturalized U.S. citizen around the year 1888. It seems unfortunately likely that Eshigami's naturalization application was denied.

Despite the evidence Japanese people lived in Eureka at the time, The Humboldt Times apparently found it newsworthy when Japanese were spotted in the city — perhaps to reassure its readers these were not expelled Chinese who had returned. On July 22, 1888, the Times stated, "We have noted a number of Japanese on our streets during this week. They are seamen and came here as sailors on vessels that are laid up." One such sailor got into difficulty here, as reported in the March 13, 1889, Times: "A Japanese sailor was before the bar of justice yesterday for being drunk and disorderly. He paid a $6 fine."

Then, on July 27, 1889, a brief, startling article appeared in the Times: "The Japanese colony of this city left, bag and baggage, by the steamer North Fork yesterday morning. We can get along without them. The passenger list shows that there were fifteen of them."

Research has not identified the 15 members of this Eureka "Japanese colony." Despite the Times' smugly racist declaration, "We can get along without them," those people's departure did not mean the end of Japanese presence in 19th century Humboldt. For example, on Oct. 10, 1889, a person identified only as "Japanese girl" was listed among the incoming passengers who arrived in Eureka on board the steamer Pomona. There is also an obscure reference in a December of 1889 Times article about the fundraising Christmas fair held by the Ladies' Aid Society of Eureka's First Congregational Church: "The coffee booth conducted by three handsome Japanese ladies was liberally and well patronized, and owing to the cold temperature, rather left the ice cream booth in the cold." One wonders if these "Japanese ladies" were members of the Eureka "Japanese colony" who had not, in fact, departed — and if one of them was the anonymous Japanese girl who arrived in October — or if they were instead white Ladies' Aid Society members wearing Japanese-inspired clothing.

Other Japanese people made brief appearances in the county during the 1890s, and departed swiftly due to the rising tide of anti-Asian racism. In December of 1895, Humboldt newspapers reported on seven Japanese men traveling through Trinidad to begin work for the Gold Bluff Mining Co. These men, The Ferndale Enterprise noted, "did not stay long. They were waited upon and told that their presence was not wanted, and they decided to depart while they could do so in good order."

The 1900 U.S. Census listed no Japanese people in Humboldt County. (Despite the widely held belief that all Chinese Humboldters had departed, the census shows five Chinese men who remained in Humboldt, living in Klamath and Orleans.) However, if it is true that no Japanese lived in Humboldt in 1900, that did not remain the case for long. According to "Situations Wanted" ads in the Humboldt Times, at least two Japanese sought jobs as cooks in this area in January of 1906. One of them, who gave his name as "Charley," described himself as, "Best Japanese cook, who has worked in hotels and private families for many years, wishes situation as cook; speaks English."

The year 1906 is remembered in California history for the devastating San Francisco earthquake. Humboldt County felt the impacts of the April 18 quake in many ways, one of which was an embarrassing racist assault on the world's leading earthquake expert.

Dr. Omori Fusakichi of Tokyo's Imperial University arrived in San Francisco in mid-May, sent by the Japanese government to study the effects of the massive quake. He journeyed to Humboldt in early July and checked into the Vance Hotel on Second Street. The July 7 Humboldt Times reported as part of a lengthy article on the distinguished scientist:

Dr. Omori stated that eleven minutes after the earthquake in California they knew it in Japan, the vibrations being recorded by their instruments. ... Not only did the doctor know that Mother Earth was shaking somewhere but by calculation [he] learned that California was the locality visited, and that the tremblor was one which did great damage. While it was several days before Humboldt knew that San Francisco had suffered, Tokio knew of it eleven minutes after the occurrence.

Omori's eminence did not protect him from a run-in with a Humboldt County racist. Setting out from the Vance for a bit of sightseeing, he was accosted by a man "who appeared to be a laborer" (as the Times reported). This man demanded to know if he'd arrived on board the steamer Corona, supposedly thinking Omori was a strike-breaking non-union sailor. He then knocked Omori down with a punch to the face, "to the astonishment of the seismic specialist, who immediately sought the hotel and postponed any further sight-seeing." Omori was apparently "good-humored" about the assault and his misidentification as a non-union sailor, but the Japanese consul was not. As soon as word of the attack reached San Francisco, the consul telegraphed Eureka Mayor A. W. Torrey to demand an investigation.

When Omori set out by train for Ferndale to study the earthquake's impacts there, he carried with him an effusively apologetic letter from Torrey. The letter read, in part,

That this assault was the result of an unfortunate mistake due to the labor troubles now prevailing on this Coast does not in anywise excuse its heinousness and brutality; and the writer, in offering you on behalf of his community a full apology for the regrettable occurrence, wishes to ... assure you that the people of this community do not uphold nor countenance such outrageous and unlawful acts ...

For several days, the Times carried a notice posted by future Eureka Mayor Hiram Ricks, offering a $30 reward for "information that will lead to the arrest and conviction of the person who assaulted Dr. Omori, the distinguished Japanese visitor in this city."

Later that year, Ricks would be a member of Eureka's "Committee of Fifteen" who directed the county's so-called "Second Chinese Expulsion." Widespread racist protests greeted the attempt by a Ferndale and Astoria-based salmon packing company to bring a crew of Chinese, Japanese and white workers to the cannery at Port Kenyon. Although the 23 Chinese cannery workers were sent back to Astoria a few days after their arrival in Humboldt, the four Japanese members of the crew were apparently permitted to remain at Port Kenyon throughout the salmon season, alongside their white colleagues.

Like an echo of what was probably the first meeting between Humboldters and people from Japan, Japanese acrobats and jugglers performed in Eureka again in 1909. "The Sugimoto troupe of seven world famous Japanese acrobats, contortionists, tight rope walkers and lofty tumblers," as they were described in the Times, headlined at the Empire Theatre in January. That July, the Empire again hosted a Japanese performer, this time "Kawana, the Japanese Juggler."

It's possible that some Japanese Humboldt residents were among the audiences for these performances. In 1909, the Times' classifieds again showed the presence of Japanese people in this county, including two different men who advertised in May for jobs in cooking or housework. That August, a resident of 1406 I St., Eureka, ran an ad seeking "A good Japanese cook" and promising "good wages." An ad in September stated, "A Japanese boy, gentle and honest, wishes position as cook, ten years' experience hotels and families, wages $50 and up." The advertiser specified that only "first class people" need answer his ad.

In October of 1909, the Times reported that an Agent Maloney from the State Bureau of Labor Statistics was visiting Humboldt. Maloney told a Times reporter that he had found "few of the lower classes of foreigners in Humboldt and even these men seem to be anything but transients." The reporter continued, "Thus far Mr. Maloney has discovered one Chinaman in Humboldt and eight Japanese laborers."

The "one Chinaman" was probably Charlie Moon of Klamath, the most well-known Chinese Humboldter who'd succeeded in remaining through the 1880s expulsions. If Maloney indeed only "discovered" this one Chinese resident, he was apparently not looking very hard. The 1910 U. S. Census would again list five men living in Klamath and Orleans who had been born in China, most of them the same men who were listed there in 1900.

In late October, The Humboldt Times ran an ad for a new Eureka business: the "Tsuchiya Brothers Company Japanese Art Store." This store, according to the ad, would carry "Porcelain, Brass and Bronze Wares, Embroidery, Drawn Work and all kinds of Fancy Goods." In addition, a "Shipment of Kimoni [sic]" had "arrived today." The store was located at "Fifth Street, near E," an address with resonance in Humboldt County Asian history. Before the 1885 expulsions, Eureka's main Chinatown area was located between Fourth and Fifth streets and between E and F.

The new store's owners are not identified in their ad or in subsequent newspaper coverage with any more specific names than "the Tsuchiya brothers," and research has thus far failed to find further information on them. Their store was only open for three days at most. Around 2:45 a.m. on Oct. 24, 1909, as the Times reported that day, "a dynamite bomb, or other explosive, was thrown into the doorway of the Japanese store." The Times continued in far less than sensitive terms, "This is the first Japanese store to be opened in Eureka, and some person opposed to the invasion of Eureka by the brown men took criminal means of venting his feeling."

The Tsuchiyas lived in a room behind their store. When one of them ran to investigate the bombing, he found himself almost gunned down by police officers Hamann and Gow, who had just arrived on the scene. Fortunately, the officers missed and Tsuchiya managed to convince them he was not the guilty party. The only evidence found was "a short piece of slow fuse, evidently part of a fuse used in exploding the bomb."

On Oct. 26 Eureka's Mayor Lambert made a statement to The Humboldt Times:

Yesterday I telegraphed to the Japanese Consul in San Francisco, expressing my regret that an attempt should have been made to wreck the establishment of the Tsuchiya brothers of this city ...

At the meeting of the Council this evening, I shall ask that a liberal reward be offered for the apprehension and conviction of the guilty party or parties responsible for the outrage.

... A few of our citizens have expressed the opinion that I should call a mass meeting to adopt a resolution condemning the atrocity; but I believe the action of the Council will fully represent the sentiments of our people ... No state of emergency exists, and there would seem to be no probability of further molestation of the Tsuchiya brothers.

Although the reward fund contributed to by local individuals and businesses eventually totaled more than $1,000, no culprit was apprehended. In addition, at 8:30 a.m. on Nov. 1, a letter was mailed at the Eureka Post Office, addressed to "g r georgeson, real estate man," the agent for the Brett Building in which the Tsuchiya brothers' store was located. This anonymous and unpunctuated letter read:

this is to warn you that if the japs stay here we will send them all to hell and you will go with them it was your fault that they opened up here and you had better see that they go away as no one has any use for you anyhow and if you value your life and property you had better use your influence or the japs and georgeson will go together.

Georgeson told the Times that he was "not in the least affrighted by the letter;" however, "for regard of his client's property," he had "terminated the lease of the Japanese art dealers." The Tsuchiyas held a sale and disposed of much of their stock, and on Nov. 18 the Times reported they would "leave this afternoon on the steamer State of California for San Francisco, where they will remain for a short time and then journey east to Boston to enter business." Research has not yet discovered whether they followed through on this plan.

Despite the unknown bomber's desire to rid Eureka of them, the 1910 census showed seven Japanese men living in Humboldt, all but one in Eureka. Sateo Hayashi, 28, worked as a cook for a private family and lived at an un-numbered address on Fourth Street. Henry Iwamasa, 34, and Kurasuke Hayakawa, 30, shared a house on Pine Street; both worked as cooks. Thirty-two-year-old Frank Neshiyama, whose occupation was listed as house servant, lived at 36 Fourth St. Y. Nishigawa, 30, was a cook in a restaurant and boarded with the family of Tom Tenneson, a deckhand from Norway. The one Japanese listed outside of Eureka was 27-year-old Henry Shiraishi, who lived in Scotia Township and worked as cook and servant for a saloon keeper.

Although these seven men lived and worked in Humboldt the year after the Tsuchiyas' store was bombed, their presence in the 1910 census seems to mark the end of an era in Humboldt County's Japanese history.

Around 1915, a guidebook was published claiming that Humboldt County had no Chinese or Japanese residents. This claim was clearly false as regards the Chinese, since at least three of the Chinese-born men who were listed in Humboldt in the 1910 census are still shown there in the census of 1920. But it may be true in the case of the Japanese. No one born in Japan, or of Japanese ancestry, is shown in Humboldt County in the 1920 census, or in those of 1930, 1940 or 1950.

Alex Service (she/her) is the curator at the Fortuna Depot Museum.

more from the author

-

Return of The Valley of the Giants

- Nov 2, 2023

- More »

Latest in News

Readers also liked…

-

Through Mark Larson's Lens

A local photographer's favorite images of 2022 in Humboldt

- Jan 5, 2023

-

'To Celebrate Our Sovereignty'

Yurok Tribe to host gathering honoring 'ultimate river warrior' on the anniversary of the U.S. Supreme Court ruling that changed everything

- Jun 8, 2023