[

{

"name": "Top Stories Video Pair",

"insertPoint": "7",

"component": "17087298",

"parentWrapperClass": "fdn-ads-inline-content-block",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

}

]

George Landgren was not a good husband or father. In 1913, he abandoned his wife, Alma, and their two little boys, and headed south. When the local sheriff forced him back to Humboldt County to care for his family, he spent just enough time with them to avoid being charged with desertion — and to impregnate his wife with their third child. When Alma died after an illegal abortion on Oct. 31, 1913, instead of grieving that evening, Landgren attempted to extort the man he thought responsible, threatening to accuse him of murder if he didn't pay up.

By 1910, Alma Landgren seemed to have known where her marriage was headed and had been working as an apprentice in a Eureka drugstore, but having two young children in quick succession likely made working difficult. When she found herself pregnant again in 1913, the prospect of having another child must have been terrifying but the solutions weren't much better. Women had few job opportunities and a single mother even fewer. A third child would have made employment untenable, so Alma sought an abortion. "Illegal operations," as they were often called, were dangerous and against the law. Alma sought help from 76-year-old Edward Goyer. A graduate of three medical colleges, Goyer had practiced medicine for more than 30 years, but his reputation had been marred by suspected ethics violations, and "nervousness" ended his professional medical career in 1901. By 1913, his health was declining and he boarded in a Eureka rooming house.

Alma's death made the news when Goyer was charged with murder, suspected of committing the abortion that ended her life. According to the Humboldt Times, which followed the court proceedings in November and December of 1913, it was the first case of its kind in Humboldt County.

An autopsy and inquest had revealed that sometime the week of Oct. 27, 1913, Alma had an abortion — and the blunt instrument used in the procedure had punctured her uterus, creating a hole about the size of a quarter. She then suffered "untold and constant agony" for days before dying of peritonitis, a bacterial infection and common cause of abortion-related deaths before antibiotics were available.

Goyer's trial and weeks of damning testimony followed his arrest, but when Alma Landgren's housekeeper told the court that Alma had performed her own abortion, prosecutors stalled. With no one to speak in the young woman's defense, all charges against Goyer were eventually dropped and he was set free.

Because it was Illegal

At the turn of the 20th century, those who found themselves with an unwanted pregnancy included married couples struggling to feed already hungry families, young women tricked or pressured into compromising their "virtue" after a promise of marriage, and victims of rape and incest. While an abortion was a risky gamble, the consequences of an unwanted child were often certain: shame, ostracism, financial struggle and regret. Death, a Colorado journalist argued in 1890, might be a "happy refuge" for "fallen" women and the risks of abortion preferable to becoming "the mother of an infant, who for life would be branded with the most hateful epithet in the English language." In other words, a bastard.

The illegal procedures were offered by doctors, men pretending to be doctors, midwives and caring relatives hoping to help a young woman move on to live a "respectable" life. While many undoubtedly cared about their patients, too many were only after money. And there was plenty to be made. While some abortionists charged as little as $25 in the early 1900s, many wanted $100 or more, the equivalent of $3,000 to $4,000 today. It was a steep price for a single girl or young couple struggling to make ends meet, but many raised the funds.

A Woman from Humboldt

In May of 1921, a judge dismissed the 32nd felony charge against San Francisco doctor George W. O'Donnell, who had been accused yet again of performing an "illegal operation." His patient? A woman from Humboldt. Something must have gone wrong to catch the attention of law enforcement, but the judge said there wasn't enough evidence to charge him.

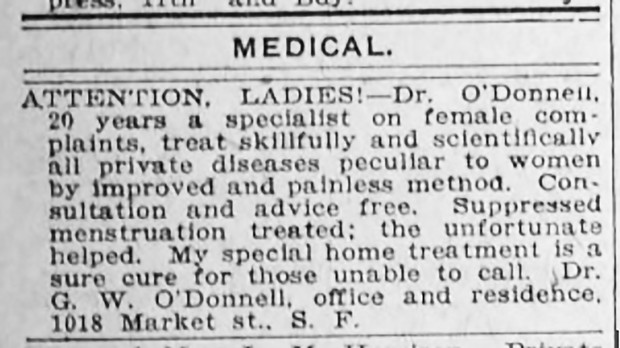

O'Donnell had been a drug dealer and opium user for years. By 1921, he had also been performing illegal abortions for more than a quarter-century. Women found him through word of mouth and ads in the San Francisco and Oakland newspapers promising to skillfully and painlessly treat "private diseases peculiar to women," including "suppressed menstruation" and "the unfortunate."

O'Donnell first made the news in the spring of 1895 when Sacramento resident Lizzy Mae Burke was seduced (or raped) by a local businessman and became pregnant. She hid her condition from her parents and traveled to San Francisco and O'Donnell's home for an abortion. When her parents finally tracked her down at the doctor's residence, Lizzy was desperately ill. They took her to St. Luke's Hospital, where she died from the "effects of a criminal operation."

The 26-year-old doctor was charged with murder but was acquitted due to a lack of evidence. It would be the first of at least two murder charges O'Donnell would escape without a conviction.

O'Donnell had followed in the footsteps of his father, Dr. C.C. O'Donnell, who was first accused of performing a similar procedure on Mary Nolan in 1890. Nolan, thankfully, survived. In that instance, the elder O'Donnell, like many abortionists, was acquitted because, as a reporter for the Coronado Mercury noted at the time, there were seldom any witnesses except the doctor and the victim. And if the woman lived, the reporter added, she could refuse to testify to avoid self-incrimination and her own criminal charges. In the Nolan case, the girl bravely testified but the judge ruled participant testimony insufficient for a conviction.

By June of 1921, the younger O'Donnell had been accused of performing 34 abortions and, in August of that same year, a 35th charge was also filed and then dropped. The man continued to practice at least until 1930 and it is impossible to know how many women were harmed and ultimately died under his care.

Cover Up

Clearly, the risks of illegal abortions by unregulated providers were immense. Many abortions were done in hidden clinics and secret backrooms. Accidental punctures of vital organs were not uncommon and sometimes inexperienced abortionists left fetal or placental material behind, which then became septic. The 1916 Journal of the American Medical Association recounted one incident in which a practitioner used forceps to extract fragments of placenta after an abortion and instead pulled out a loop of the woman's intestine.

Because the procedure was illegal, providers faced with complications or a maternal death often focused on self-preservation. In 1897, after Pearl Bryan died of an abortion in Illinois, Scott Jackson confessed to working with at least two other men to decapitate the woman and bury her head in a sandbar alongside a river, all in an attempt to thwart her identification and avoid prosecution. In 1910, after San Francisco doctor Robert Thompson performed a fatal abortion on Paso Robles school teacher Eva Swan, he poured nitric acid on her body and buried her in his cellar. Though Humboldt County readers were spared many of these stories, in 1914, the Humboldt Times ran a wire service story about a Pennsylvania abortion clinic known as the "House of Mystery." Officials believed an untold number of women died at the facility from botched abortions and their bodies were burned in the basement furnace. Because illegitimate pregnancy was so stigmatized and abortion illegal, women seldom told their family or friends of unplanned pregnancies or plans to end them. As a consequence, many women who died of abortion complications were never identified and their families never notified.

And So it Continued ...

While there continued to be individual practitioners, abortion "rings" with statewide networks were gaining popularity in California by the 1930s. In 1939, Margaret Sanger, a pioneer birth control advocate, estimated at least 8,000 women were dying every year from abortions, a majority of them married and already parenting three or more children. In 1965, outcomes were no better. The U.S. Department of Health, Education and Welfare reported that of the 1,189 total maternal deaths per 100,000 reported that year, 235 — almost 20 percent — were caused by complications arising from illegal abortions.

By 1967, California lawmakers had had enough and then-Gov. Ronald Reagan signed the state's therapeutic abortion law, which made the procedure legal in cases of rape and incest, or when the pregnancy presented a danger to mother's physical or mental health. The state Assembly ordered the state Department of Public Health to evaluate the impact of the new law and, in 1968, the department reported there had been minimal change in the number of legal abortions performed. In the two months evaluated, 254 women received abortions under the new guidelines: 18 because of rape, seven because of incest, 214 due to mental conditions and 15 to avoid risks to the mother's physical health. As proof that California had not turned into an abortion mill, the report added, only four of the women receiving services lived outside the state. The number of Illegal abortions being performed, on the other hand, was harder to gauge. At the time, the department estimated 20,000 to 120,000 illegal abortions were still occurring in the state each year. In 1969, women in California finally secured the right to legal abortions when the state's Supreme Court found (in People v. Belous) that women have a fundamental right to choose whether to bear children under both the California and United States constitutions.

Roe V. Wade

In May of 1970, "Jane Roe," an unmarried woman who wanted to safely end her pregnancy, filed a lawsuit against Texas District Attorney Henry Wade claiming that abortion laws were unconstitutional. Though the case took two and a half years to resolve, on Jan. 22, 1973, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Roe's favor, declaring women had a constitutional right to abortion under the 14th Amendment.

This milestone event paved the way to better and safer universal abortion access, though the challenges were not over. Though many doctors estimated legal access to abortion reduced maternal mortality by 50 percent, anti-abortion activists continued to protest access and many — especially conservative and/or isolated communities — had limited or no access to care. These barriers, however, gave rise to some unexpected pro-choice supporters. On Oct. 24, 1976, the Times-Standard reported that Rosalynn Carter and President Jimmy Carter, both ardent Christians, supported the right to choose after they witnessed the effects of illegal abortions in Georgia and "saw women whose bodies were permanently damaged by illegal operations in abortion mills."

History Repeats

Rove V. Wade was overturned on June 24 and many states have taken advantage of the ruling. According to the New York Times, as of Jan. 6, 13 states had fully banned abortion and Georgia limits access to women who are less than six weeks pregnant. These recent changes have ignited concerns that maternal deaths will rise again as desperate women turn to now-illegal, unlicensed and unregulated abortion providers.

Lynette Mullen (she/her) is a Humboldt County-based writer and historian. Visit preservinghistories.com to learn more.

more from the author

-

Opium Dens and 'Morphine Fiends'

Humboldt County's current opioid epidemic parallels its first

- Jun 16, 2022

-

The Emerald Gang

- Jun 16, 2022

- More »

Latest in News

Readers also liked…

-

Through Mark Larson's Lens

A local photographer's favorite images of 2022 in Humboldt

- Jan 5, 2023

-

'To Celebrate Our Sovereignty'

Yurok Tribe to host gathering honoring 'ultimate river warrior' on the anniversary of the U.S. Supreme Court ruling that changed everything

- Jun 8, 2023