'A Segregated Campus'

Frustrations mount at Cal Poly Humboldt as ADA issues go unaddressed

By Thadeus Greenson [email protected] @ThadeusGreenson[

{

"name": "Top Stories Video Pair",

"insertPoint": "7",

"component": "17087298",

"parentWrapperClass": "fdn-ads-inline-content-block",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

}

]

For a thought experiment, imagine for a moment what the community response would be if a building housing one of Cal Poly Humboldt's departments only allowed men to enter. Imagine what people would say if dozens of bathrooms across campus were labeled "whites only." Or, what if the university decided to remove the gender neutral restrooms that dot the campus.

If you're envisioning large, organized protests and boycotts, Aaron Donaldson wonders where they are. The hypotheticals above may feel absurd, but Donaldson, a lecturer in the university's Communications Department, says they mirror the reality facing him and other faculty, staff, students and community members with physical disabilities and mobility issues on a campus ridden with access barriers.

"If it said 'Whites Only' or "Men Only,' it'd be a huge problem, but people don't see ableism," says Donaldson, standing in front of the Telonicher House, a two-story structure without ramps or lifts that houses his entire department, pointing to the "Walkies Only" signs he's affixed to its two exterior stair cases. "This is a segregated campus."

Cal Poly Humboldt's accessibility issues drew local media attention last year when a former student filed a lawsuit alleging the campus was unsafe for people with disabilities, which Donaldson and others hoped would prompt the university to address the myriad of access issues already on its radar. But the lawsuit settled out of court, and the issues remain.

In one of its final acts of the 2023-2024 school year, the University Senate passed a four-page sense of the senate resolution calling for transitioning to an accessible campus that called on the university to address a handful of issues before the next school year. Specifically, the resolution called on the university to correct potentially dangerous errors in its online accessibility maps, which are designed to help people with disabilities chart safe paths through campus, and to update them to include the locations of accessible bathrooms. The resolution also called on the university to post evacuation instructions for people with disabilities in all multi-story buildings on campus.

With the fall semester now underway, none of that has been done, and frustrations are growing.

Jim Graham has been immersed in accessibility issues pretty much his whole life. Around the time he was born, his father lost his right leg to amputation after a lifelong battle with osteomyelitis and later went on to start the National Amputee Skiers Association, and his mother taught special education. Graham himself cut his teaching teeth tutoring hearing impaired students before leaving Chico State University with a degree in computer science and math, while walking on knees that have been damaged from birth and periodically dislocate.

Graham says he then went to work for Hewlett Packard and was there when the landmark Americans with Disabilities Act passed in 1990, declaring that "state and local governments must provide people with disabilities an equal opportunity to benefit from all of their programs, services and activities." The ADA quickly came to consume Graham's professional life, as he was tasked with training the company's 3,000 employees on the company's new ADA policies over the course of about a year.

"It radically changed the organization in just a few years," he says. "It was very impressive to see and I loved being a part of it."

But Graham tired of the private sector and went back to school to get his PhD, studying geographic information system, and in 2013 took what he describes as a "dream job" teaching at Cal Poly Humboldt. But Graham says he was on campus for years before he realized the extent of the university's ADA problems.

"The embarrassing part is I missed how big the issues were," he says. "I was focused on getting tenure when I got here, and the geospatial program was going through some changes and I was crazy busy."

Like many on campus, Graham says he simply walked by many of the problems, failing to notice missing signage, inaccessible doorways, unsafe walkways and other things because they did not directly impact him. Graham says it wasn't until the spring semester of 2023 that the issue became a priority, pushed forward by two people who addressed the University Senate, of which he was a member.

First, there was Christine DiBella, a student who'd transferred to the university in 2021, who told the senate the university lacked evacuation chairs for wheelchair users in multi-story buildings, and described "dehumanizing" situations like facing an automatic door that won't open, being unable to find an accessible bathroom or finding an accessible pathway blocked or impassible.

"It is not my responsibility to request these things," DiBella told the senate. "I am entitled to them."

Then, a few months later, Donaldson also addressed the senate, explaining that he lives with "ongoing and regressive problems" in his spine, knees, ankles and hips that are uncomfortable, inoperable and affect his mobility. Donaldson told the senate he'd faced a "culture of indifference" since arriving on campus in 2015.

Graham says he was moved by Donaldson and DiBella's comments, and followed up with them both. Pretty quickly, he says, other students, staff and community members started reaching out to him.

"I didn't solicit issues," he says. "They just found out through word of mouth that I was listening, so they came to me with issues. What I heard was that there are accessibility issues on campus and when people try to make changes, either they're met with resistance or there's no response."

And the list kept growing, so Graham says he took it upon himself to find out more.

"I'm an engineer so I did what engineers do: investigate the problem to find out what's real and gather data," he says. "I like fixing problems."

Graham says he got to work on the resolution the senate ultimately passed May 7, and helped reconstitute the university's Committee on Accessibility and Accommodation Compliance, which had stopped meeting due to COVID-19 and never resumed. The goal, he says, was to launch a collaborative effort to begin addressing the myriad of issues people had brought forward.

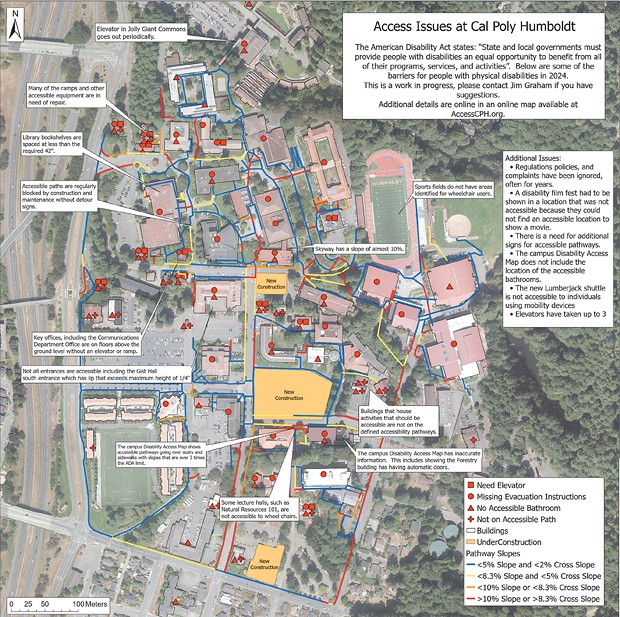

He then spent the summer walking the campus, measuring running slopes and cross slopes of walkways on campus to gauge which are safe for people using wheelchairs, which can tip over if slopes are too steep. He started a website, accesscph.org, to field tips and document his findings, putting together an "access issues" map that Donaldson and others feel is the most comprehensive inventory of the campus' access issues available.

The map is an aerial view of campus overlayed with symbols and lines, with red indicating pathways that are impassable for people using wheelchairs due to stairs or steep slopes and blue denoting pathways within ADA regulations. Buildings on the map are denoted with symbols indicating whether they're missing elevators, evacuation instructions or accessible bathrooms, as well as notes of particular issues, like that the library bookshelves are spaced less than the required 42 inches apart, making them impossible to navigate for some wheelchair users.

Graham says the more he's learned and documented, the more frustrated he's become at the pace of improvements. He says some things have changed for the better — saying the university now has more and clearer access information online and has streamlined the approval process for the campus' access shuttle, reducing wait times from six weeks to two days, to name a few. But progress has been slow, he says, and pervasive problems remain.

"The big thing that we don't seem to be doing is we don't seem to be addressing the physical barriers, specifically in existing structures," Graham says.

Donaldson set foot on the Cal Poly Humboldt campus for the first time in the fall of 2015, arriving sight unseen, having accepted an offer to lecture in the university's Communications Department and coach its famous debate team.

"I was really excited to be here," he says.

But that excitement quickly diminished when he toured Telonicher House, its main floor accessible only by two exterior staircases, as well as another one inside. In addition to the physical barriers, Donaldson says he noticed things indicating a culture that didn't value access and inclusion, like the exterior sign telling wheelchair users who to call for accommodations located on the door at the top of one of those exterior staircases.

"I saw that building right away was not accessible, and I saw that sign at the top of the stairs and thought that was terrible," says Donaldson, recalling the irony of his tour guide pointing out the gender neutral bathrooms on the building's second floor. "I didn't really say anything but I was shocked. And I was worried about the stairs."

Donaldson says he moved into an office on the ground floor but had to traverse the stairs to visit other members of the department, access the debate room or use the printer. He says he was nervous to say anything until he got a multi-year contract with the university but when he did, he says he was quickly made to feel like he was the problem, like he was being unreasonable. Told adding ramps to Telonicher House was impossible or too expensive, Donaldson says his office was eventually moved to Founders Hall so he wouldn't have to walk the stairs. But he says he feels isolated and segregated from the rest of his department, frustrated his colleagues won't demand the department be moved to an accessible building.

"It makes me feel like a problem," he says.

And that's the sense Donaldson says he's gotten repeatedly when bringing up access issues on campus. After moving his office to Founders Hall, he says he noticed ornamental shrubs along Laurel Drive had overtaken the handrail on the sidewalk and began sending emails asking they be trimmed only to get no response for months.

"It's alienating as someone who needs railings not to fall down to see people walking by without caring," he says. "That's inherently alienating."

While the topography of Cal Poly Humboldt's campus has long been the stuff of legend — while known as HSU, students would joke the letters stood for Hills and Stairs University — Donaldson dismisses the notion it's inherently inaccessible. He says he's visited plenty of campuses with debate teams and none have the types of issues he sees locally, noting that Lewis and Clark College in Portland is similarly hilly yet entirely accessible.

"It's not the age of the campus at all," he says. "It's not the geography of campus at all. It's a cultural problem."

As an example of this cultural problem, some point to the Behavioral and Social Sciences building, which, built in 2007, is a relatively new addition to campus and entirely accessible, built to the ADA's requirements. The problem is there's no accessible foot path connecting it to the rest of campus, meaning people using a wheelchair must catch the shuttle to get there, when the university could have simply installed a ramp adjacent to an existing staircase, as it did to provide an accessible pathway to Founders Hall.

Loren Canon, the past president of the California Faculty Association's Humboldt chapter who now serves as its chair of faculty rights, says the university simply has to prioritize making the campus accessible to everyone. According to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, more than 12 percent of adults in the nation have mobility issues with serious difficulty walking or climbing stairs, and Canon says accommodating them is simply an equity issue.

"It's the law, right?" Canon asks. "These are non-negotiables, that our campus should be welcoming and accessible to everyone. It's got to be prioritized."

On Sept. 12, 2023, the lawsuit DiBella filed against Cal Poly Humboldt and the California State University system settled out of court, with the CSU admitting no liability and agreeing to pay $230,000 ($180,000 of which went to DiBella's attorneys) on the condition that DiBella withdraw from school and never reapply.

The settlement brought a quiet end to the lawsuit, which alleged that the university had failed to provide accessible facilities, excluded her from student social events and that the CSU lacked emergency evacuation plans for students with disabilities. DiBella told the Journal in a 2023 interview she was told there would be evacuation chairs in the residence halls when she applied, and was shocked to find there were none when she arrived on campus.

Around the same time DiBella settled her lawsuit, the University of California at Berkeley held a fire drill that left Ryan Manriquez stranded in his wheelchair on the second floor of a building. Manriquez shared his story with the University of California Board of Regents a few weeks later, prompting UC President Michael Drake to offer a "personal apology," promising the problem would be rectified on all UC campuses before the board's next meeting.

Cal Poly Humboldt, meanwhile, still has not installed the chairs — which cost about $2,000 apiece — in its residence halls and other multi-story buildings. DiBella declined to comment for this story.

"I fully support Aaron Donaldson and Jim Graham's efforts and feel strongly that the Humboldt community deserves an accessible, equitable and inclusive campus," she said in a text message explaining her decision. "I am abstaining from commenting to allow space for others' voices and bring focus to broader equity issues."

The Journal reached out on Aug. 28 to Cal Poly Humboldt's marketing and communications office for information on what work has been done in recent years to improve accessibility on campus, and request other information for this story, but was told it couldn't meet the paper's Sept. 2 deadline because "the person who can help answer these questions is out." A subsequent inquiry asking who that person is was not returned.

For his part, Donaldson says he believes a high degree of turnover in campus administration has contributed to problems getting issues addressed, noting the university's current interim ADA coordinator primarily works remotely.

Donaldson spent a couple of hours on each of the first few days of school handing out printouts of Graham's accessibility map to students and others passing by Telonicher House. One of the last people he approached was acting Cal Poly Humboldt President Michael Spagna, who was just days into the job, having recently taken over for outgoing President Tom Jackson Jr.

Spagna, a former special education teacher, took one of the maps and told Donaldson to set up a meeting with his office, saying he wanted to learn more. Donaldson says he's not terribly hopeful, but noted some of the problems that need addressing are as simple as putting up signs or updating the accessibility map, so if Spagna decides to take the issue seriously it should be evident pretty quickly.

"I'm just really angry," Donaldson says. "I feel like this is a huge and important story and when I stop talking about it, it goes away."

Shortly before the Journal went to press Sept. 3, Graham, clad in a beige baseball cap and jeans, addressed the University Senate during its public forum to report he'd received "a veiled threat of potential legal action" after sharing the access website he'd created with university administrators.

In his brief remarks, Graham echoed much of what he'd told the Journal the week prior, but with a more transparent level of frustration and additional detail, including how a student was left "injured and bleeding" when their wheelchair fell over on campus and how he'd watched another leaning out of their chair to avoid falling over when rounding a corner.

Graham told the senate that through multiple interactions with Michael Fisher, the university's acting vice president of Facilities Management, he'd come to understand "his approach to accessibility" is to adhere to the Americans with Disabilities Act's Title I and the California Building Code, both of which only apply to new construction projects or major alterations of existing structures. But Title II of the ADA, which passed in 2011, requires organizations to provide individuals with disabilities access to all their programs and activities, Graham said.

This underscores a core point Graham had made when speaking to the Journal, the idea that the university is reticent to make any access improvements unless explicitly required to do so. ("The problem when I talk to facilities is they say, 'That's existing and we don't have to fix it,'" he told the Journal. "My position is, 'We have to make it accessible.' Theirs is, 'We don't have to unless it's new.'")

Graham told the senate he'd spent part of the summer working with a group of school administrators on an ADA transition plan, "something that was required 30 years ago."

"We made some progress on the plan but then [Facilities Management] stopped attending the meetings and we need their expertise to estimate the cost of projects," Graham said, adding that he's heard the university allocated $400,000 for ADA improvements and he understand there are other grant opportunities.

He also recounted his work surveying the campus over the summer, giving senators a flier detailing issues he found with the Natural Resources Building, in which he teaches, and errors on the university's disability access map. He noted that while the building's lecture hall has a wheelchair accessible desk, the hall itself is only accessible via two staircases. Additionally, he said the path identified as accessible on the university's map in front of the Natural Resources Building goes down a flight of stairs.

"I raised issues about the map almost one and a half years ago but it has not changed," he said. "I offered to work with Facilities [on the maps] but my emails were not returned. I then created a personal website with access to the maps at AccessCPH.org and I let the administrators I have been working with know that the site is available. I was then surprised to receive a veiled threat of potential legal action against me."

Graham told the senate he decided to address them because it's the only way he knows of to share his views with a broad group of campus leaders.

"To summarize, our university is and has been dangerous to individuals with physical disabilities and especially those using mobility devices," he said. "This is made worse by having an online map that shows them an accessibility path that goes down stairs and over slopes that are far too steep."

Graham closed by saying that the university is successful when it works collaboratively to resolve issues that are raised. But when it retaliates against the people raising the issues, "the issues do not go away and folks may feel forced to contact the media, have protests and pursue legal action against the university."

As Donaldson hands out maps on Aug. 28, he's greeted with a variety of responses. Some students hustle past, saying they're late for class and really need to keep moving. Some nod approval when he approaches them talking about ADA issues on campus, saying something like, "I know, it's terrible," as they keep moving. Others stop and engage.

When done for the day, Donaldson notes that he teaches more than 130 students every semester and, because he teaches public speaking and critical thinking, which all students are required to take, his students should be a pretty representative cross section of the campus' enrollment. He says he's never taught a student who uses a wheelchair, likely because prospective students who visit campus look around and feel unsafe or unwelcome, or maybe just look at campus maps and see that they don't include the locations of accessible restrooms and quickly realize those running the campus don't have their needs in mind.

Donaldson says Graham's work to document accessibility problems has been a rare bright spot in his time on campus, calling Graham simply a "hero." He says years of trying to get these issues addressed have taken a toll. Yes, he says, he's angry that these problems haven't been fixed, but he's even angrier that nobody else seems to be angry, that he and people like DiBella are left to stand alone, fighting for access, as a community that says it values diversity, equity and inclusion walks by. If that doesn't change, Donaldson says, nothing else will.

Before leaving campus for the day, Donaldson pauses and turns back to the Journal reporter he's been talking to.

"I'm going to ask you to come back in one year because I'm going to tell you, in one year, nothing will have changed," he says. "And that's the fucking story."

Thadeus Greenson (he/him) is the Journal's news editor. Reach him at (707) 442-1400, extension 321, or [email protected].

more from the author

-

Eureka City Schools to Talk Jacobs, Grand Jury Response

- Aug 29, 2024

-

'Loss'

Mad River Hospital's birth center to close, igniting layered concerns about a healthcare system in 'crisis'

- Aug 29, 2024

-

Eureka City Schools to Talk Jacobs, Grand Jury Response

- Aug 27, 2024

- More »

Latest in News

Readers also liked…

-

'To Celebrate Our Sovereignty'

Yurok Tribe to host gathering honoring 'ultimate river warrior' on the anniversary of the U.S. Supreme Court ruling that changed everything

- Jun 8, 2023

-

Pride in Full Stride

- Jun 29, 2023