[

{

"name": "Top Stories Video Pair",

"insertPoint": "7",

"component": "17087298",

"parentWrapperClass": "fdn-ads-inline-content-block",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

}

]

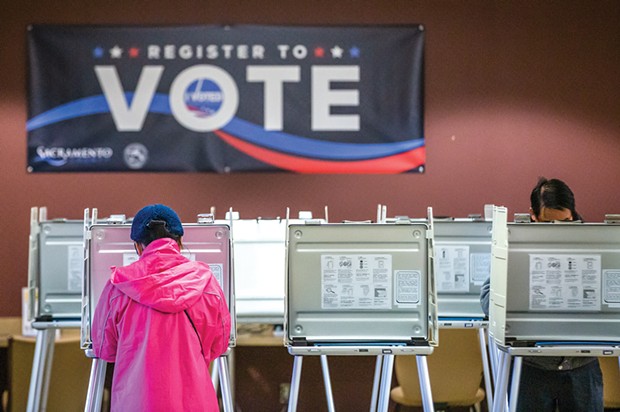

Much is expected of the California voter.

In any given election year, we may be asked to dust off our labor lawyer hats, brush up on oil and gas regulations, reacquaint ourselves with decades of tax policy, or analyze infrastructure funding. We may have to weigh the moral pros and cons of capital punishment, marriage equality or pig protection and — over and over again — oversee all things dialysis clinic.

This November, voters will decide the fate of 10 thorny policy proposals, including crime, health care, rent control and taxes. This year, there were far more last-minute changes than usual.

Five measures were withdrawn by their proponents in deals with lawmakers, and another was kicked off the ballot by the state's highest court. And Gov. Gavin Newsom scrapped a crime measure at the last minute.

But on the final day possible, legislators added two bond issues, one for climate action and another school construction. The 2024 ballot will be more crowded than 2022, when only seven measures appeared, the fewest in more than a century.

What are all these propositions really about? How did they make their way to the ballot in the first place? And how did Californians first fall in love with direct democracy?

Here is California's passion for propositions, explained.

What's on Your November Ballot?

After months of signature gathering, litigating and legislative wrangling, the final list of measures on the Nov. 5 ballot is set. The Legislature directed the Secretary of State's Office to assign numbers to several, and the office set the others. (Reminder: Proposition 1 was Newsom's mental health measure that narrowly passed in March.)

Proposition 2: Borrow $10 billion to build schools. Legislative Democrats put on the ballot a bond issue to give $8.5 billion to K-12 schools and $1.5 billion to community colleges for construction and modernization.

Proposition 3: Reaffirm the right of same-sex couples to marry. This constitutional amendment from the Legislature would remove outdated language from Proposition 8, passed by voters in 2008, that characterizes marriage as being between a man and a woman.

Proposition 4: Borrow $10 billion for climate programs. Legislative Democrats also placed a bond issue on the ballot that includes $3.8 billion for drinking water and groundwater, $1.5 billion for wildfire and forest programs and $1.2 billion for sea level rise. In part, the money would offset some budget cuts.

Proposition 5: Lower voter approval requirements for local housing and infrastructure bonds. This constitutional amendment from the Legislature would make it easier for local governments to borrow money for affordable housing and other infrastructure. To avoid opposition from the influential real estate industry, supporters agreed to block bond money from being used to buy single-family homes.

Proposition 6: Limit forced labor in state prisons. Lawmakers added this one late — a constitutional amendment to end indentured servitude in state prisons, considered one of the last remnants of slavery. The California Black Legislative Caucus included the amendment in its reparations bill package.

Proposition 32: Raise the state minimum wage to $18 an hour. This initiative seemed a much bigger deal when it was first proposed in 2021. But under existing law, the overall minimum wage has risen to $16 an hour. And lower-paid workers in two huge industries are getting more: Fast food workers received a $20 an hour minimum wage on April 1 and health care workers will eventually get $25, though the start date has been pushed back to at least Oct. 15.

Proposition 33: Allow local governments to impose rent controls. This is the latest attempt to roll back a state law that generally prevents cities and counties from limiting rents in properties first occupied after Feb. 1, 1995.

Proposition 34: Require certain health providers to use nearly all revenue from a federal prescription drug program on patient care. Sponsored by the trade group for California's landlords, this measure is squarely aimed at knee-capping the AIDS Healthcare Foundation, which has been active in funding ballot measures (see the rent control one above).

Proposition 35: Make permanent a tax on managed health care insurance plans. This initiative is sponsored by California's health care industry to raise more money for Medi-Cal and block lawmakers from using the cash to avoid cuts to other programs. The measure would hold Newsom to a promise to permanently secure that tax money for health care for low-income patients.

Proposition 36: Increase penalties for theft and drug trafficking. This initiative may be the most contentious on the ballot. It would partly roll back Proposition 47, approved by voters in 2014, instituting stiffer penalties for some drug and theft offenses.

Last-minute Deal-making on Measures

By 2014, California voters were sick of ballots larded up with too many measures, many of them highly technical, specific to one industry or difficult to understand.

So state lawmakers changed the rules. While initiatives can only go before voters in November, a tweak to the election code gave the Legislature more time to hold public hearings on those upcoming measures, while giving initiative backers the chance to revise or remove initiatives later in the process. The goal was a more deliberative, thoughtful process with more room for compromise.

But one person's "compromise" is another person's "legal extortion."

The most notorious example came in 2018 when the soda industry funded a ballot measure that would have made it much more difficult for local governments to raise taxes. They pulled the initiative — which then-Gov. Jerry Brown called an "abomination" — after lawmakers agreed to ban new local soda taxes for the next 13 years.

Then in 2023, the Legislature passed a law allowing similar deal-making on referendums to overturn existing laws. It was immediately used to pull a fast food industry referendum off this November's ballot, and used again by the oil industry to abandon its referendum to kill a ban on drilling near homes, schools and other sensitive areas.

Prior to this year, a total of nine measures had been withdrawn from the ballot after qualifying; the most for any single election was three in 2018.

But this year, five compromises were struck to pull measures off the ballot before the June 27 deadline. After business and organized labor made a deal to change a California-only state law that allows workers to sue their bosses over alleged workplace violations, business groups withdrew a measure to repeal the law completely. The governor's office also brokered pacts with the proponents so that they stood down on initiatives to fund pandemic preparedness through a tax on multi-millionaires and to expand state funding for health care for critically ill children. And after the Legislature passed a similar proposal, a nonprofit executive pulled his initiative to require a financial literacy class to graduate from high school.

Separately, in a highly unusual and controversial decision, the California Supreme Court removed a sweeping anti-tax measure in response to a lawsuit by Newsom and legislative leaders.

A Little History Lesson

By Sameea Kamal

California is one of 26 states with either an initiative process, referendum process or both.

While the state has had some way for citizens to initiate laws since 1898, it formally adopted the ballot initiative process after a special election on Oct. 10, 1911, when then-Gov. Hiram Johnson signed into law the ability for voters to recall elected officials, repeal laws by referendum and to enact state laws by initiative.

The push for more direct democracy was part of a movement across the U.S. in the late 1800s for social and political reform. In California, it was fueled by concerns over the influence that Southern Pacific Railroad and other "monied" interests had over the Legislature.

From 1911 through the most recent ballot measures in November of 2020, there have been 2,068 initiatives cleared for signature collection. Of those, 392, or about 19 percent, qualified for the ballot. And of those that made the ballot, 137, or 35 percent, have been approved by voters, including 39 constitutional amendments.

The most measures on a single ballot? Forty-eight in 1914, followed by 45 in 1990 and 41 in 1988.

What's the difference between a referendum and an initiative?

A referendum allows voters to approve or reject a statute passed by the Legislature, but with some exceptions: "urgency" statutes necessary for public peace, health, or safety; statutes calling elections; or laws that levy taxes or provide appropriations for current expenses.

Initiatives, which are more common than referenda, propose new statutes, as well as amendments to California's constitution. Since 2011, initiatives can only appear on the November general election ballot.

In most cases, initiatives and referenda share the same signature requirements — at least 5 percent of the total votes cast for the office of governor at the last election. A constitutional amendment initiative, however, requires at least 8 percent of the total votes cast at the most recent gubernatorial election.

For this election, that was at least 546,651 signatures to qualify an initiative, and 874,641 for a constitutional amendment.

The Long and Winding Road to the Ballot

By Sameea Kamal

What can be an initiative? Anything that's the "proper subject of legislation" — as long as it only addresses one subject.

To get an initiative or referendum on the ballot, there are a few steps that can begin more than a year before the election.

• An idea is proposed by citizens to the state attorney general's office with a $2,000 fee, or a bill is passed by the Legislature.

• A title and summary are written by the attorney general.

In California, unlike in some other states, the ballot title and summary are not drafted by the secretary of state or an elections board. The language is meant to be neutral, but former attorneys general Xavier Becerra and Kamala Harris, and current Attorney General Rob Bonta, have been accused of not always staying impartial.

For example, a parents' rights group sued over the title of its proposed initiative to require schools to notify parents if their child identifies as transgender, to ban female transgender students from girls' athletic teams and to prohibit children from medically transitioning. Bonta labeled it as "Restricts Rights of Transgender Youth" and a judge upheld his description. Subsequently, proponents failed to gather enough signatures to qualify their initiative for the ballot.

(A proposed initiative to transfer the drafting authority to the nonpartisan Legislative Analyst's Office failed to qualify for the 2022 ballot. And a bill this year to do the same also failed.)

• Signatures are gathered. The number of signatures required is based on a percentage of total votes in the last gubernatorial election.

• Lawmakers are alerted, after which they may hold public hearings. The Legislature is not allowed to amend the measure or prevent it from appearing on the ballot, but a 2014 law allows more room for compromise for proponents to withdraw qualified measures from the ballot.

• Collected signatures are verified by the secretary of state's office. This is done in two ways, once measure proponents file at least 100 percent of the required signatures to qualify. Under the random sample method, each county elections office is required to verify at least 500 signatures or 3 percent of the number of signatures filed in their office, whichever is greater. If the completed sample shows that the number of valid signatures is projected to be more than 110 percent of the required signatures, the measure qualifies. If it's less than 95 percent, the measure fails to qualify.

If the number of valid signatures in the random sample represents between 95 percent and 110 percent of the required total, then the full check method requires election officials to verify every signature on the petition filed with their office.

Campaigns pay anywhere from $2 to $6 per signature to petition gatherers, depending on how well-funded the campaign is, and how close they are to the required number of signatures and the deadline. Over the last two years, due to COVID-19 safety measures and the labor shortage, the price per signature could rise to as much as $15, some strategists told the Los Angeles Times.

A statewide ballot measure is approved by a simple majority vote of the people.

Big Money, Big Interests

By Ben Christopher

The founding story of the California ballot measure is an electoral tale of David versus Goliath. In 1911, progressives introduced the initiative statute, the referendum and the recall as a way to wrest ultimate lawmaking authority away from a corrupt Legislature and bestow it upon the electorate.

But from the early days, Goliath learned how to fight back.

"The controlling factor is money," said Glen Gendzel, a history professor at San José State University who has written about the early history of Californian direct democracy. "If it's a pay-to-play system, then those who have the most money are going to play the most."

In 1920, white agricultural interests helped sponsor a measure banning Japanese immigrants from owning farmland. In 1926, the dairy lobby waged an expensive war against margarine producers. Throughout that decade, private utilities helped defeat three efforts to establish a public hydroelectric power agency. As early as 1923, a special legislative committee came to a depressing conclusion about California's experiment with direct democracy: "Victory is on the side of the biggest purse."

That wasn't always the case — nor is it today. Sometimes the appearance of trying to buy a law can backfire. In 2010, PG&E spent nearly $50 million — more than 300 times the opposition — on a campaign to make it more difficult for local governments to set up their own public power agencies. The utility lost.

In recent years, many business interests have gone to the ballot not just to advance their own policy goals, but to reverse the work of California's increasingly Democratic Legislature. That strategy paid off for ride-hailing app companies and bail bond agents in 2020, when both industries spent millions to undo state laws aimed at transforming or outlawing their business models.

No doubt cigarette and vape liquid manufacturers were taking note. In 2022, they funded an effort to nix a state ban on flavored tobacco. While voters overwhelmingly rebuffed them, that still bought them time. As soon as a referendum qualifies for the ballot, the law that it targets is put on hold. And because state law only allows referendums during regular general elections, that reprieve can last as long as two years.

Why the Ballot Can be Confusing

By Sameea Kamal

It's possible for multiple measures on the same topic to appear on the ballot — even ones that conflict with each other. If one is approved by voters and the others are rejected, it's simple: The approved one takes effect. And if several pass and they don't conflict with each other, they all go into effect.

But if multiple measures pass that conflict, the measure or provision of a measure that receives more "yes" votes is the one that goes into effect.

In November of 2022, that would have been the case with the big-money battle between competing online sports betting measures, one sponsored by national giants in the industry, the other by some Native American tribes. But voters rejected both measures decisively, though the campaigns spent more than $570 million combined, nearly twice the previous record.

One of the most recent examples was in 2016, when there was Proposition 62 to repeal the death penalty, but also Proposition 66 to speed up the appeals process for capital punishment by putting trial courts in charge. Because 51.1 percent of voters approved Proposition 66, it superseded Proposition 62, approved by only 46.8 percent.

In 2010, Proposition 20, a measure adding congressional redistricting to the duties of an independent redistricting commission, competed with Proposition 27, which aimed to disband the commission. Proposition 27 failed.

And on the 1988 ballot, Californians faced five competing initiatives on car insurance reform. Voters passed just one. Also in 1988, Proposition 68 and Proposition 73 went head-to-head on the regulation of political campaign contributions. Proposition 73 received more "yes" votes, and after a legal battle, the California Supreme Court ruled it would take effect — only to be later tossed out by another lawsuit.

This story was initially published by CalMatters, a nonprofit, nonpartisan newsroom dedicated to explaining California policy and politics.

More by Ben Christopher

More by CalMatters

-

Behind the 'No Corporate PAC' Pledge

Are California Senate candidates really swearing off corporate dollars?

- Feb 15, 2024

-

New State Laws Aimed to Streamline Home Building Take Effect in 2024

- Jan 4, 2024

-

'Things Have to Change'

Even as dams are coming down, Klamath Basin ranchers, tribes battle over water

- Dec 21, 2023

- More »

Latest in News

Readers also liked…

-

Through Mark Larson's Lens

A local photographer's favorite images of 2022 in Humboldt

- Jan 5, 2023

-

'To Celebrate Our Sovereignty'

Yurok Tribe to host gathering honoring 'ultimate river warrior' on the anniversary of the U.S. Supreme Court ruling that changed everything

- Jun 8, 2023