[

{

"name": "Top Stories Video Pair",

"insertPoint": "7",

"component": "17087298",

"parentWrapperClass": "fdn-ads-inline-content-block",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

}

]

Jan. 24, 1984, Bellingham, Wash. Around 2 p.m. I take a break from the water system I'm designing and walk downtown to our local computer store -- someone's told me they're unveiling a fancy new machine there. I join a group of rubberneckers standing around a beige box, two feet high, a foot on each side. It's the first Macintosh, 128K of on-board memory, no hard drive (what's a hard drive?), 400K floppy disks to take care of both applications and data ... and my life changes forever.

Three months later and now a proud owner of a Mac 128K, I remember telling a friend that this was going to change my life. Within a year I was no longer calling myself an engineer: my card said, graphic designer. (If you wear a cowboy hat, you can call yourself a cowboy.) Curiously, though, the first thing that impressed me wasn't the machine itself but its mouse, a magical device (at the time) for intuitively moving an arrow around on the Mac's nine-inch black-and-white screen. No more painfully entering coordinates to shift from one location to another, as in previous computers I'd used. Now, the arrow perfectly mimicked the movement of your hand.

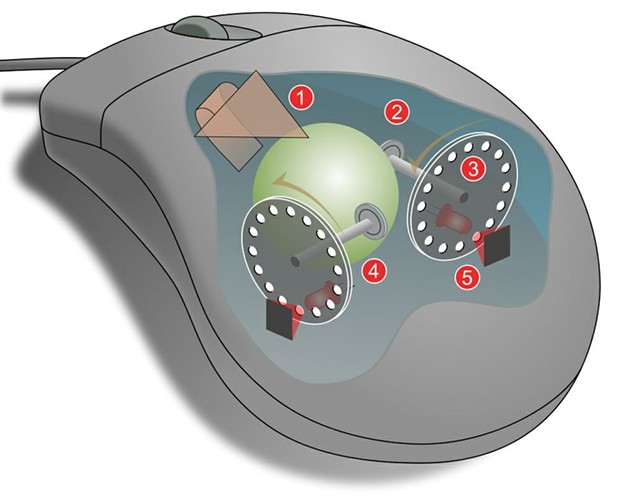

What I didn't know is that the mouse had already been around for 20 years. In 1963, 38-year-old inventor Douglas Engelbart, working at the Stanford Research Institute in Menlo Park, asked his lead engineer, Bill English, to build a prototype mouse that tracked movement with two perpendicular wheels attached to analog potentiometers.

Nine years later, now at Xerox PARC in Palo Alto, Bill English designed a mouse with a metal ball instead of wheels. The ball turned two rollers that connected to the $32,000 Xerox "Alto" computer. In late 1979, in return for a pre-IPO stock deal, Xerox gave Apple three days of access to PARC. When Apple co-founder Steve Jobs saw the lastest Alto, he could barely contain his excitement at his first sight of "gooey" (-GUI, graphical user interface): windows, menus, radio buttons, check boxes and icons -- all controlled by a mouse channeling an arrow on the screen. (Malcolm Gladwell tells the story in the May 16 New Yorker.)

The next day, Jobs commissioned industrial designer Dean Hovey to create a $15 mouse -- that's 5 percent of the cost of the Xerox mouse. ("What's a mouse?" asked Hovey, whose next stop was the Mountain View Walgreen's, where he bought every rolling-ball underarm deodorant he could find.) Four years later the Mac debuted, including Hovey's trackball-with-optical-encoder-wheel mouse. And I was smitten.

The mouse hasn't stood still since. The first optical mouse (no ball) was invented in 1981, also at PARC. Ten years later, Logitech released the first radio-frequency wireless mouse (they've since sold more than a billion). And in 1996, Microsoft popularized the scroll wheel in the IntelliMouse.

Englebart never received royalties for the mouse. SRI patented it and licensed it for $40,000 to Apple, who were so sure of the Mac that they paid $1.5 million to air Ridley Scott's "1984" Macintosh ad during Super Bowl XVIII. Best commercial ever, at youtube.com/watch?v=OYecfV3ubP8.

Barry Evans ([email protected]) returned to his Apple roots with an iPad 2.

Comments (5)

Showing 1-5 of 5

more from the author

-

The Myth of the Lone Genius

- Jun 6, 2024

-

mRNA Vaccines vs. the Pandemic

- May 23, 2024

-

Doubting Shakespeare, Part 3: Whodunnit?

- May 9, 2024

- More »