[

{

"name": "Top Stories Video Pair",

"insertPoint": "7",

"component": "17087298",

"parentWrapperClass": "fdn-ads-inline-content-block",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

}

]

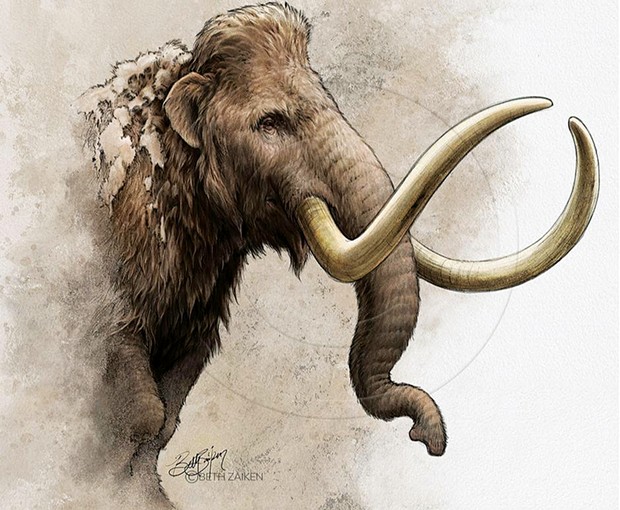

When I asked self-styled "museum artist" Beth Zaiken if I could use her evocative painting of a mammoth for a story, she was quick to point out that the image I attached was not just a mammoth, it was a woolly mammoth. Turns out, mammoths came in many shapes and sizes, with woolly mammoths particularly celebrated over other species because they were the last to go extinct. Indeed, we have over 500 early depictions of woolly mammoths in dozens of caves in Spain, France and Russia, the earliest of which were painted 35,000 years ago. (Anatomically modern humans are thought to have reached Europe nearly 50,000 years ago.)

Cave paintings are just one way we know about these magnificent creatures. They are, in fact, the best studied of all extinct animals because so many frozen carcasses have been found, mostly in Siberia and Alaska. For thousands of years, they co-existed with humans, leading to speculation that our ancestors hunted them to extinction. Best bet is that it was a combination of over-hunting and climate change, the latter greatly reducing its habitat. They nearly made it to the present, though! Although most groups went extinct soon after the end of the most recent ice age, around 11,500 years ago, some isolated populations survived much longer. A herd living on Wrangel Island, the large Russian island northwest of the Bering Strait, probably survived until 4,000 years ago, meaning they were around for a good thousand years after the Nile pyramids were built.

Mammoths are typically shown in movies and cartoons as living in a snowy wasteland, but their actual habitat was "tundra steppe," similar to today's Russian steppes. They were herbivores, spending up to an estimated 20 hours a day eating grasses and sedges to support their intake of up to 400 pounds of food a day, putting them in the same dietary class as modern elephants. Their adaptations to the cold included (of course) hairy coats — actually two coats: long "guard hairs" on the outside overlaying a short, softer undercoat, which in turn covered a 4-inch layer of fat just under the skin. Their short ears and tails helped minimize heat loss and frostbite. They lived to about 60 years old.

Most of the news about mammoths these days discusses the click-bait possibility of resurrecting the species — that is, bringing woolly mammoths back to life using DNA from soft tissue material and hair follicles in their frozen corpses. That became a talking point after the genome was completely mapped about a decade ago, when researchers showed that extinct woolly mammoths and extant African elephants share about 99 percent of their genomes.

One promoter of this idea, aptly named Colossal Biosciences, explains on its website that it plans to: "Use gene editing tools that work like scissors to cut [African] elephant DNA and provide a mammoth sequence to incorporate into elephant cells in the same location." Reinsert the engineered egg into the uterus of the unwitting mom-to-be and 22 months later, the elephant's calf is born with woolly mammoth genes. Whether there's enough usable DNA in long-dead, frozen mammoths is debatable, as is the morality of the venture. Happily (for this writer), several prominent geneticists have come out in opposition to this kind of "if we can do it, we should do it" caprice. If the de-extinction effort is successful, a wildlife reserve in Siberia, given the hopeful name "Pleistocene Park" (shades of Jurassic Park), has been designated as a future home for the de-extincted critters.

One final tidbit: The word "mammoth" probably derives from "mehemot," Arabic for "Behemoth." In the biblical Book of Job, the Behemoth was said to be one of the two monsters created by God early in creation, the other being Leviathan, a monster whale. Which is somehow fitting for one of the most majestic creatures to have ever lived.

Barry Evans (he/him, [email protected]) would prefer to let sleeping mammoths lie.

Speaking of...

-

Sheriff's Office Identifies Wayne Adam Ford Victim After 25 Years

Jun 7, 2023 -

Mastodons in Greenland

Feb 16, 2023 -

Dinosaurs Died, Mammals Thrived

Dec 15, 2022 - More »

more from the author

-

From Mars Believer to Skeptic, Part 2

- Aug 15, 2024

-

From Mars Believer to Skeptic, Part 1

- Aug 8, 2024

-

The Other Evolutionist

- Jul 25, 2024

- More »