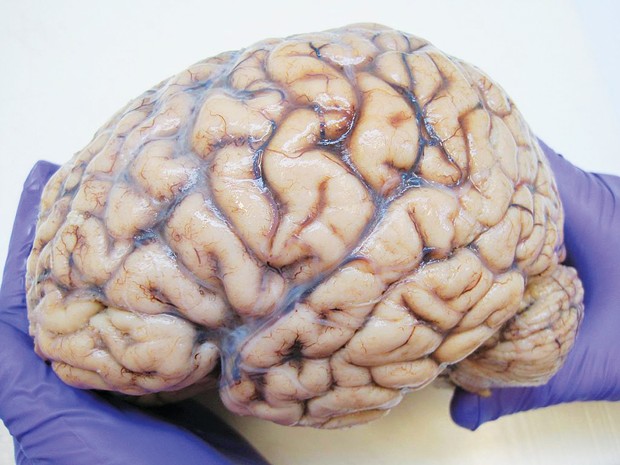

Photo by Jensflorian, Creative Commons via Wikipedia

Autopsied human brain. Does all that folding and furrowing make us smarter?

[

{

"name": "Top Stories Video Pair",

"insertPoint": "7",

"component": "17087298",

"parentWrapperClass": "fdn-ads-inline-content-block",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

}

]

"The brain is a 3-pound mass you can hold in your hand that can conceive of a universe 100 billion light-years across."

Marian Diamond, neuroscientist

In 2021, a peer-reviewed scientific study made headlines in the popular press: Human brains shrunk by about 5 percent between 5,000 and 3,000 years ago. Taken at face value, this is pretty shocking, since back then our ancestors were just starting to deal with the complexities of city-states, writing and large-scale food production. If anything, you'd think brains would increase in size to compensate for a more sophisticated lifestyle than simply hunting and gathering in small, tight-knit communities. As we'll see, the study's conclusions aren't quite so cut and dried as originally presented.

Seven million years ago, Sahelanthropus, the newly bipedal creatures that would eventually spawn you and me, had brains about a quarter the volume of modern humans, that is, about 350 cubic centimeters (cc) compared with around 1,400 cc today. By the time of Homo habilis some 2 million years ago, brains were 600 cc, doubling in size in the next million years to around 1,200 cc (Homo heidelbergensis) before settling down with our species, Homo sapiens, 300,000 years ago, at around 1,400 cc.

Oddly, Neanderthal brains were even larger, up to 1,750 cc, begging the question: Doesn't a bigger brain mean greater intelligence? Neanderthals were smart, with more clues to their intelligence found regularly. We know, for instance, they created jewelry, buried their dead and made sophisticated spear points and other stone tools. That is, they were probably as smart as the contemporaneous people that became us, only dying out due to outside circumstances, perhaps falling prey to diseases carried by Homo sapiens. (You're probably carrying 2-4 percent of Neanderthal genes, so they didn't go entirely extinct.)

In any case, brain size isn't everything. A sperm whale has the largest brain in the animal kingdom — 18 pounds of brain to control a 45-ton beast — so clearly a larger body needs more brain-power. What makes more sense is to compare brain-to-body weight ratio, which is about 1:5,000 for the sperm whale, compared with about 1:40 for humans and rodents. The record holder is a tiny ant, Brachymyrnexm, whose brain to body mass is 1:8. And having a large brain comes at a cost; in humans, for instance, our 3-pound brains — that is, about 1/50 of our weight — are metaphorical gas guzzlers, since about 25 percent of our total metabolism goes to the brain.

Back to the incredible shrinking brain. Turns out, data used by the original researchers was skewed, comparing apples to oranges and weighting the results with too many measurements of skulls from just the last 100 years. When corrected for flaws, the data shows no recent reduction in brain volume. As Brian Villimoare, one of the anthropologists who re-analyzed the original study, put it, "... based on this data set, we can identify no reduction in brain size in modern humans over any time period since the origins of our species."

But even if they had shrunk, big brains don't automatically mean more intelligence. One theory holds that our brains got more convoluted as they squeezed into skulls, resulting in previously unlinked neurons becoming connected — perhaps leading to speech or fancier tools or artistry? That is, maybe the evolution of this stuff in our skulls is more about better-connected brains than bigger brains.

Barry Evans (he/him, [email protected]) thinks intelligence is a one-way ticket to the extinction of our species.

more from the author

-

Woolly Mammoths: The Lady's Not for Cloning

- Aug 29, 2024

-

From Mars Believer to Skeptic, Part 2

- Aug 15, 2024

-

From Mars Believer to Skeptic, Part 1

- Aug 8, 2024

- More »