[

{

"name": "Top Stories Video Pair",

"insertPoint": "7",

"component": "17087298",

"parentWrapperClass": "fdn-ads-inline-content-block",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

}

]

"Last night."

— Fictional lone genius Tony Stark answering when he became an expert in thermonuclear astrophysics

If you believe everything you see on the silver screen, you know all about lone geniuses. Think Tony Stark, Doc Brown (Back to the Future) and Zefram Cochrane (Star Trek's warp drive inventor). No harm done there but problems arise when real-life characters are burdened with the same "lone genius" tag beloved of screenwriters. Three that come to mind are John Nash (A Beautiful Mind), Alan Turing (The Imitation Game) and Nikola Tesla (Tesla). Truth is, these so-called lone geniuses collaborated with colleagues and benefited from previous work. Same, for instance, with Albert Einstein, Galileo Galilei and Alfred Wegener.

I mention Wegener because twice in the last week, his name came up to justify some maverick scientist's wacky theory: the debunked idea that vaccines cause autism, that a freak asteroid proves the existence of intelligent alien life, that Noah's flood really happened. It goes like this: "100 years ago, German meteorologist Alfred Wegener, working alone, was scorned by other scientists, when, having noticed that the coastlines of Africa and South America match, proposed that the two continents had once been joined and were now drifting apart ("continental drift"). Decades later, other scientists saw the error of their ways and embraced his theory. Thus proving that a maverick lone genius is often right and mainstream science wrong."

While it's true that some scientists — mostly "hard rock" geologists, who probably didn't appreciate being upstaged by a mere meteorologist — discounted continental drift, many others took his ideas seriously enough to convene conferences on both sides of the Atlantic to consider it. Wegener's 1915 book The Origin of Continents and Oceans went through five printings — hardly a sign of indifference. Meanwhile, two of the preeminent geologists of the day, Émile Argand in Switzerland and Arthur Holmes in England, embraced Wegener's theory despite many problems with it.

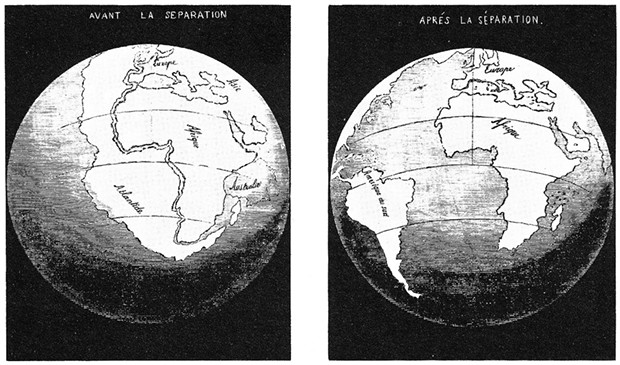

First, though, Wegener was hardly the first to wonder about the matching coastlines of South America and Africa, starting with Abraham Ortelius in 1596. Later, Antonio Snider-Pelligrini mapped the spread of the Atlantic in 1858. (See illustration.) So Wegener was building on a long tradition. Even his claim that all the continents had once been joined together in one great landmass, "Pangea," wasn't original: That had been proposed in 1889 by Roberto Mantovani. Second, he was hardly a loner, since most of his life was spent working with university colleagues.

The main problem with continental drift was that Wegener was unable to come up with a convincing mechanism to explain it. Additionally, he overestimated by two orders of magnitude how fast the Atlantic Ocean is spreading (8 feet vs. 1 inch per year), and he proposed much else that conflicted with known data at the time. It took until the 1960s (long after Wegener's death, in 1930) for the theory of plate tectonics to be universally accepted. Although at first blush, this looks like Wegener's continental drift, it really isn't. Plate tectonics is a new paradigm. In a nutshell: Earth's rigid outer shell consists of about seven major (and many minor) "plates" which float on the plastic mantle beneath. At the boundaries, the plates may be moving apart (like seafloor spreading along the mid-Atlantic ridge) or converging (like the Pacific plate plunging beneath the North American plate off our shore) or they may slide past each other (like the San Andreas fault).

None of this was understood by Wegener and his contemporaries, since they lacked the data provided much later by deep-sea cores and the magnetic "striping" thus found (that's for another column), but the bottom line is, he was no lone genius. Like nearly all advances in science, it took decades of collaborative work to turn Wegener's questionable idea of continental drift into the well-grounded theory of plate tectonics.

Barry Evans (he/him, [email protected]) first heard about the plate tectonics revolution in 1962, in his university geology class.

more from the author

-

mRNA Vaccines vs. the Pandemic

- May 23, 2024

-

Doubting Shakespeare, Part 3: Whodunnit?

- May 9, 2024

-

Doubting Shakespeare, Part 2: Problems

- May 2, 2024

- More »