[

{

"name": "Top Stories Video Pair",

"insertPoint": "7",

"component": "17087298",

"parentWrapperClass": "fdn-ads-inline-content-block",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

}

]

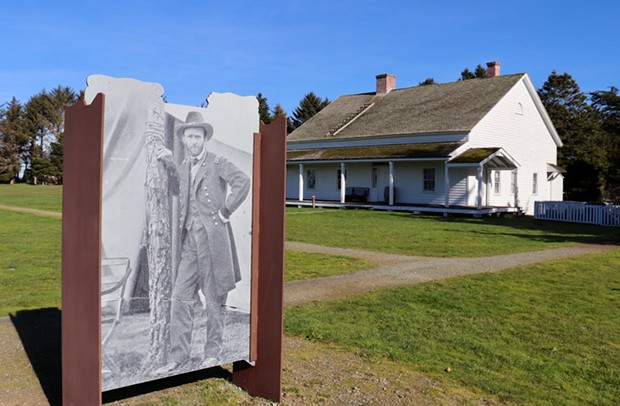

We walk through our world in the footsteps of those who came before, sometimes treading the same path unaware. As a teen, I visited the Ulysses S. Grant home in Galena, Illinois. As an adult I helped with an historical recreation of the dinner U.S. Army pork supplier William "Hog" Ryan threw for his friend President Grant in Dubuque, Iowa. Years later, I found myself gazing at the visage of Grant once again. He and I found ourselves far from the Mississippi River, both standing on the grounds of Fort Humboldt State Historic Park, separated by nearly 170 years.

When I chose the just over half-mile loop, I didn't know that I would find this old acquaintance. I did find what I expected in a state park steeped in history. Interpretive panels let the curious investigate and the incurious pass unaffected. People with the need for speed can leg it past leisurely ramblers counting steps as families picnic.

The easy path rolls by the fort's only surviving original building, the hospital built in 1863. At the building's rear, I spied a sentry peering through a window but he was only an illustration. Another window holds illustrations of period surgical instruments that make one appreciate modern medicine. The museum inside is undergoing renovation, so my partner and I lingered over these window-framed treats. We strolled up the porch ramp to see Dr. Lafayette Guild, who left Fort Humboldt to serve in the Civil War as General Lee's personal physician. The wide porch framed the parade grounds and I admired the hospital's little garden, an essential for growing medicinal herbs before antiseptics were discovered.

Quartermaster Grant served in the commissary, its former site located by a panel with a photo of Grant 10 years later, in the easy pose of a man who has hit his stride. I pictured him, bleary-eyed after hiding in the tavern, maybe yearning for his wife and contemplating what he thought was a bleak military future. In 1854, an unhappy Grant resigned his captaincy promotion after only five months. He left Humboldt to eventually settle in Galena, Illinois, where our paths originally intersected.

We left the general behind in pursuit of new knowledge, peering through the windows of the reconstructed surgeon's quarters where Harriet St. John Simpson lived with husband Assistant Surgeon Josiah Simpson and their children. She chronicled her life at the fort from 1854 to 1857, sharing cooking instructions along with social commentary. An earlier panel highlighted the work of women, showing the partnership needed to survive and thrive. I still shudder at the workload of the indomitable laundress.

We turned onto the ramrod-straight path that passed the site of living quarters — company, officers and commander — its focal point a tall wooden pole where soldiers once raised and lowered the flag to the tune of a brassy bugle. The standing tent panel is just what kids love. The flaps are permanently open, enticing an energetic 3 year old to sidle through while allowing an older sibling to contemplate the rough life of the ordinary soldier. Farther along, a white doorframe reveals brass beds and wine — the perks of being an officer.

Fort Humboldt was built to protect gold, lumber and settlers, but it tore the nation's fabric. Major Gabriel J. Rains is said to have tried to keep settlers from harming Native people but his attempts to mend the rip failed. The fort overlooks the site of Goutsuwelhik, one of five Wiyot villages settlers wiped out in 1860, murdering hundreds of people. It was a hard fact to digest on a sunny day, as was this quote on the panel by Albert James, Wiyot: "Ever since the massacre, the shells have never heard the Indian song."

The plight of the Wiyot, already shocking, worsened after the federal troops were sent east where their fates again intermingled with Grant on Civil War battlefields. The replacement soldiers were recruited locally and their abuse of the Wiyot is chilling. I cannot give description to the corral supposedly built to protect but instead containing such misery the Wiyot named it Jouwuchguri'm, meaning "lying down and drawing up your knees." As we read, a hiker strode past this panel and the next one describing the deadly 1935 labor strikes at the Holmes-Eureka Mill. The mill had been built on top of Goustuwelhik, long before the Bayshore Mall covered them both. The fort itself succumbed to a changing world, its buildings and mules sold off in 1870.

We were lapped by a lady quickly walking a terrier as we took refuge in the shady woods. The park's logging display provides a treat for the history buff and the metalhead. Panels throughout told tales of life in camp and the formidable Maggie and her cookhouse. Steam and diesel machines created to harvest the tallest trees on earth waited for our inspection. I wandered past massive sections of redwoods to find donkey engines invented by John Dolbeer, of Eureka. Once the powerhouses of industrial logging, they were designed to help chew up the forest and feed America's need for lumber. The brutal geometry of gears makes the iron monsters things of beauty. The towering three-story Washington slackline loader is now quiet, its thunderous part in the transformation of Humboldt County long over. Delicate ferns now accentuate the machine's cold stillness.

A weathered train shed housed two honored relics: locomotives behind plexiglass, graciously accepting the cooing admiration of an elderly couple. The history of Bear Harbor Lumber Co. 1 was rife with drama and it captivated the pair. We strolled past them and beyond, flanked by tall log arches, machines designed for low impact removal.

We neared the end of the circuit, peering through the trees, drawn to voices singing. A group of ranger hats popped into view beyond the Grant commemorative plaque. I saw young people dancing and felt a sense of rightness. As I passed a building on the way to the van, I saw a new sign and understood — the community had come together to repair the fabric a little. The sign reads: "Fort Humboldt State Historic Park is located on the land of the Wiyot people. The name for this place is Jouwuchguri'm."

We don't move on from history so much as we weave through it, adding our own threads. I smiled at two young people, one in a ranger hat, standing on a picnic table in the sun.

Meg Wall-Wild (she/her) is a freelance writer and photographer who loves her books, the dunes of Humboldt and her husband, not necessarily in that order. When not writing, she pursues adventure in her camper, Nellie Bly. On Instagram @megwallwild.

Speaking of...

-

'Our Food is Our Medicine'

Mar 28, 2024 -

Despite Coastal Commission Appeal, Schneider Mansion Demolition, Restoration Could be Complete by July

Jan 9, 2024 -

Humboldt Bay Timeline

Oct 12, 2023 - More »

Comments (3)

Showing 1-3 of 3

more from the author

Latest in Get Out

Readers also liked…

-

A Walk Among the Spotted Owls

- Apr 27, 2023