[

{

"name": "Top Stories Video Pair",

"insertPoint": "7",

"component": "17087298",

"parentWrapperClass": "fdn-ads-inline-content-block",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

}

]

It makes sense for restaurant cooks to be jealous of their best recipes. I remember years ago teaching myself to make croissants. Nena Creasy, a great cook who lived nearby above the Klamath River, even gave me a big marble slab to roll out the layers of dough with butter and then more butter. I tried making them with whole wheat flour, as though that would make them healthy, but they always flopped.

I heard of a health food bakery out along Interstate 5 that made them with whole wheat as light and flaky as their white flour cousins. I made the pilgrimage and the rumors were true. So I asked the baker how he did it. The guy exploded and almost threw me out of the joint.

I'd been a restaurant cook myself years earlier and most, but not all, the veteran cooks I knew shared everything. If somebody asked how I made our Hollandaise sauce, I'd tell them to look at page 357 in the 1979 edition of the Joy of Cooking. And I'd whisper, "Use the blender version. If you use the regular version you'll probably need two able-bodied helpers and a barometer."

In 2014, when my daughter Erica Terence was in charge of the vegetarian food at the Mid Klamath Watershed Council's annual fundraiser, she told me she was going to ask the cooks at Brick and Fire in Eureka how they made their mushroom cobbler. I thought she didn't stand a chance in the world.

At Brick and Fire, owner Jim Hughes and his staff of five to six cooks serve about 25 portions of the cobbler a day — each filled with a variety of wild mushrooms and infused but not drowned in a savory cream sauce. He likes the availability of wild mushrooms in Humboldt and has collectors who call him whenever they have a supply — especially fog-drip chanterelles.

One key to the cobbler's success is that Brick and Fire, located in an un-gentrified neighborhood along Eureka's F Street, is heir to a huge wood-fired brick oven. Hughes says it may have been the biggest factor in his decision to open the restaurant there seven years ago.

The massive oven was built 20 years ago. It measures 6 feet wide and 9 feet deep inside, and the cooks monitor the temperatures with a laser thermometer. Near the entrance it's 550°F and climbs about 100 degrees every foot closer to the flames. The cobbler cooks there quickly, very quickly.

Still, like many cooks, he is shy of spelling out the details of his recipes, including the cobbler, despite having made it on camera for Guy Fieri's Diners, Drive-ins and Dives. He says that a couple of his specialty items have already shown up on the menus at other restaurants in the community. Besides, Hughes is not a strict recipe kind of cook. "It's never the same thing twice," he says, "even though the title might be the same. I just like to keep exploring." Diners seem to find the explorations rewarding.

But when Erica talked to Hughes about the fundraiser, she said he was surprisingly forthcoming, not just with the trademark recipe, but with an invite to come work with the Brick and Fire cooks. The morning she showed up to work with the cooks was highly productive. "That's where you learn how slowly to cook the onions and little details like whether to use the better grade white wine or the other white wine."

Fortunately for the MKWC dinner, the little upriver town of Orleans has several brick ovens — none that big, but just as hot. Erica used one at Sandy Bar Ranch, a small eco-resort on the banks of the Klamath.

MKWC has crews out all over the landscape with projects on fisheries, fire protection, invasive weed control, watershed education, food security and more, and many staffers were happy to add wild mushroom collection for the mid-December fete to their chores.

It was not an easy dish to prepare, even in small portions. Still, the dish was a huge success, drawing carnivores to defect for the night. The 100 servings disappeared in a flash. Erica took it on again this winter, this time making 200 servings.

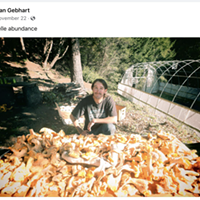

In the week before the event, volunteers, who themselves jealously guard secret hunting spots, started bringing mushrooms in. Tanya Chapple, who trained as a botanist at UC Berkeley and is director of the nonprofit's plants program, even found black trumpets, a mushroom variety prized for its taste and renowned for how hard it is to spot. Will Harling, a founder and director of MKWC, took advantage of a prime year for oyster mushrooms and contributed a bushel to the cause. Michael Eagan, who operates Mycality Mushrooms in Arcata, contributed several cases of shitakes and hericiums, the lions' mane mushrooms usually only found wild, and then inconveniently up the trunk of a tall tree. The stack grew and grew. Erica woke one morning to find a bucket of tanoak mushrooms on her doorstep. Other locals brought her chanterelles. There were also some cases of store-bought: creminis, dried shitakes and dried porcinis.

Again, it was a great success. "We still had a meat entrée," Erica said, "but we'd made so much of the cobbler that people no longer had to pretend they were vegetarians. We may take another year off before we make it again. You wouldn't want to do this too often — gallons of cream, buckets of wild harvest mushrooms."

As for replicating the dish at home, well, it took Erica more than a recipe to make the cobbler. She had neighbors with brick ovens and a flock of co-workers out in the woods during mushroom season.

I wondered the other day if I could have approached that guy years ago who baked the whole wheat croissants better than I did. I told the story to one of Orleans' great cooks. She nodded reflectively and grinned. "I can guess why he wouldn't tell you. He didn't want you to know that he mixed in white flour with the whole wheat — probably a lot. He needed to keep that secret. It was a health food place, right?"

Besides, it's a cook's right to keep secrets. I just won't tell them how I make that perfect Hollandaise.

Speaking of...

-

Mushroom Mania

Nov 24, 2022 -

Local Mushroom Hunters Come Out of the Woods on NPR

Dec 25, 2021 -

Magnificent Matsutake Mushrooms

Nov 25, 2021 - More »

more from the author

-

From Orleans to the Capitol

Spreading Good Fire

- Dec 2, 2021

-

'Given These Songs'

Native singers gather to thank Brian Tripp; he thanks them back

- Jun 17, 2021

-

Fighting Fire with Fire

A devastating wildfire season highlights the need for prescribed burns

- Nov 5, 2020

- More »