IN

THE NEWS | CALENDAR

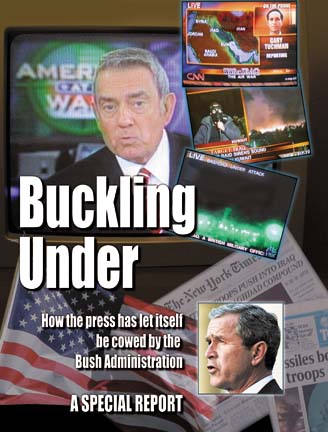

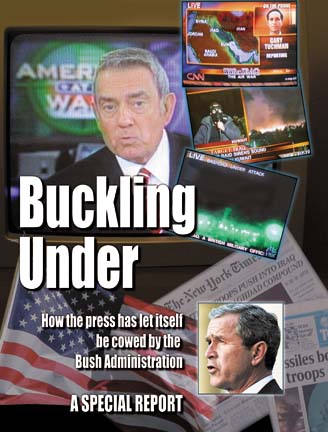

BUCKLING UNDER POLITICAL WINDS

-- and to some potent strong-arming

from the Bush administration -- the mainstream press seems more

intent these days on proving its patriotism than on dispassionately

reporting the news.

This is particularly obvious with the

televised coverage of the war in Iraq: Images of the "shock

and awe" attacks on Baghdad last week were played over and

over again while shots of Iraqi civilians wounded or killed in

those strikes were few and far between; CNN anchor Aaron Brown

seemed to apologize in advance for showing footage of the massive

anti-war protest in Chicago lest anyone's patriotic sensibilities

be offended; and whether it was Dan Rather, Tom Brokaw or Peter

Jennings, the American flag always seemed to be over their shoulder,

as if reassuring the viewer that, journalist or not, we're all

on the same team.

Most objectionable, perhaps, was the

visible excitement of anchor and reporter alike at the awesome

might of the American military. Firepower, it is clear, is sexy;

never mind that it is blowing people to bits. Also, the uniquely

American tendency to treat armed conflicts as athletic contests

was on full display: U.S. forces are the equivalent of the San

Francisco 49ers when Joe Montana was at his peak -- a juggernaut

that can't be stopped.

Lest you think the jingoistic journalism

is confined to your television screen, consider that American

newspapers all the way up to the New York Times are ignoring

a story that is major news in Europe: the bugging of the homes

and offices of United Nation's Security Council members. You

wouldn't have known it over here, but the scandal spread last

week when it was discovered that the headquarters of the European

Union in Brussels was also bugged. The No. 1 suspect? U.S. intelligence

agencies.

Presented below is a report that recently

appeared in the Bay Guardian, San Francisco's venerable alternative

weekly. It can be argued that rallying behind the troops is a

longstanding tradition in the American press: Much of the coverage

of World War II, for example, was less than objective. Nonetheless,

as the following story makes clear, there is good reason to be

concerned that the Fourth Estate, at least in this country, is

betraying its own principles.

-- KEITH EASTHOUSE

Spoon-feeding the press

The Bush

administration's unprecedented war on public information --

and how the major news media are going along.

by CAMILLE T. TAIARA,

staff writer, San Francisco

Bay Guardian

ON MARCH 2, the London Observer broke a stunning

story about the U.S. government -- a story with serious international

implications: U.S.

agents were bugging the homes and offices

of United Nations Security Council members who had not yet vowed

support for the war on Iraq. The news made headlines all over

Europe. The story was more timely and possibly more important

than the Pentagon Papers, Daniel Ellsberg, who leaked that secret

history of the Vietnam War, told columnist Norman Solomon. Yet

it did not appear in the San Francisco Chronicle until

five days later, buried on page A16 in the form of a reprint

from the Baltimore Sun. The New York Times, the

nation's paper of record, blacked out the story entirely.

The next day, the Chronicle provided

scant space to report evidence that the United States may have

falsified documents it gave U.N. inspectors indicating the existence

of certain weapons of mass destruction in Iraq -- on page A11,

under the caption "U.S. Information Wanting." On the

front cover: a prominently displayed photo of two Bay Area soldiers

tossing a football in a desert camp.

Neither story of U.S. government misdeeds

was covered adequately, if at all, in the source the vast majority

of Americans rely on for their daily news: the nation's major

television networks.

That's been a pattern since the attacks

of Sept. 11, 2001 -- and now that the United State has embarked

on a bloody war in Iraq, the utter complacency of the mainstream

press in this country has experienced observers shaking their

heads.

"The purpose of journalism is to monitor

the centers of power -- to challenge officialdom," Robert

Fisk, veteran Middle East correspondent for the U.K.'s Independent

newspaper, told us by phone from Beirut. "By and large,

the media in the United States has totally failed in its obligation

to do that. Instead of challenging officialdom, it's become a

conduit, a funnel down which officialdom can talk to us."

Part of the problem is the news media's

apparent fear of seeming unpatriotic in a time of war. That's

nothing new. But in the post-Sept. 11 environment, the Bush administration

is conducting an unprecedented expansion of government secrecy.

Under the ruse of national security, the feds have been drastically

decreasing access to even basic information about the workings

of government -- and for the most part, the media are allowing

it to happen.

Secrets in high places

Even before the Sept. 11 attacks, President

George W. Bush and his inner circle began formulating plans to

exercise greater command over information and decisionmaking

processes. It has since become the most secretive administration

in decades.

"From the time they came into office

in January 2001, it has been the position of the Bush administration

to restrict information to the public and to Congress and the

media in order to enhance what they believe is the diminished

power of the executive branch," said freedom of information

specialist Will Ferroggiaro of the National Security Archive,

a nonprofit research institute, library of declassified U.S.

documents, and public interest law firm. As an example, Ferroggiaro

cites President Bush's executive order, signed Nov. 1, 2001,

blocking the release of 68,000 presidential documents from the

Reagan era. Then there's Vice President Dick Cheney's insistence

on conducting energy task force hearings behind closed doors

-- even hearings between energy company executives charged in

the Enron scandal and government officials who were supposed

to be investigating the case.

To this day, the White House has refused

to release information on those hearings to Congress.

It's hard to make any logical connection

between protecting Enron and preserving national security. But

no matter: The Bush administration has capitalized on the Sept.

11 attacks to constrain the dissemination of information and

decisionmaking power on every level.

One year after al-Qaeda operatives flew

planes into the World Trade Center and the Pentagon, the Reporters

Committee for Freedom of the Press issued its second edition

of a report titled "Homefront Confidential: How the War

on Terrorism Affects Access to Information and the Public's Right

to Know" that includes a chilling chronology of the crackdown.

Here are a few highlights:

- Sept. 21, 2001: Chief Immigration Judge

Michael Creppy orders the closure of immigration and deportation

proceedings when directed by the Justice Department. Even family

members are not allowed to attend.

- Oct. 5, 2001: The White House narrows

the list of congressional leaders entitled to briefings on classified

law-enforcement information from the Central Intelligence Agency,

the Federal Bureau of Investigation, and the State, Treasury,

Defense and Justice Departments.

- Oct. 10, 2001: National Security Adviser

Condoleezza Rice tells network executives Osama bin Laden could

be using his videotaped messages to communicate with al-Qaeda

members in the United States.

- Oct. 12, 2001: Attorney General John Ashcroft

issues a memorandum on the Freedom of Information Act -- drafted

by his office the previous summer -- reversing Clinton-era FOIA

policy that allowed government officials to release documents

so long as doing so would not cause any "foreseeable harm."

Instead, agencies that opt to withhold records "can be assured

that the Department of Justice will defend [their] decisions

unless they lack a sound legal basis," Ashcroft wrote, in

effect discouraging the release of any information unless clearly

required by law. The Bush administration has since retaliated

against government agents who have released nonclassified information

it deemed "sensitive."

- Nov. 13, 2001: President Bush decrees

that suspected terrorists can be tried by secret military tribunals.

- Dec. 10, 2001: President Bush grants the

Department of Health and Human Services, the Department of Agriculture

and the Environmental Protection Agency the authority to classify

information.

- Dec. 27, 2001: The Bush administration

announces it will imprison suspected Taliban and al-Qaeda fighters

in Guantanamo Bay, Cuba. It refuses to release the names of the

detainees.

- n Dec. 28, 2001: The White House issues

a statement asserting the president's right to withhold any information

from Congress he deems necessary for reasons of "foreign

relations, the national security, the deliberative processes

of the executive, or performance of the executive's constitutional

duties."

- Feb. 19, 2002: The New York Times reports

Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld's intentions to disseminate

false information to the media through its new Office of Strategic

Influence. Rumsfeld eventually closes the office as a result

of public outcry but makes a cryptic statement to the press in

November indicating he intends to go forward with its misinformation

plans.

- March 19, 2002: White House Chief of Staff

Andrew Card issues a memorandum to all federal departments and

agencies ordering them to review and safeguard all data on weapons

of mass destruction as well as any other information "that

could be misused to harm the security of our nation." More

than a dozen agencies remove information from their Web sites

as a result. The memo also rewards private corporations for submitting

"sensitive" information to the government by exempting

such information from FOIA disclosure.

- April 18, 2002: The Immigration and Naturalization

Service orders the names of all INS detainees be kept secret.

Three months after the Reporters Committee

for Freedom of the Press issued its report, Congress granted

Bush the green light to create the Department of Homeland Security.

Bush signed the act Nov. 25 establishing the department, which

consolidates 22 agencies -- including the Secret Service, the

Coast Guard and what used to be the INS -- into a single, cabinet-level

entity. As it stands, the act creating the department includes

a special exemption to FOIA that allows private companies to

provide information to the DHS without that information ever

being disclosed. It also allows for criminal charges to be levied

against any federal employee who discloses "critical infrastructure

information" to the public without proper legal authorization

-- thereby undermining whistleblower-protection laws.

"Information has become consistently

more difficult to obtain, through every channel," Steven

Aftergood, editor of Secrecy News for the Federation of American

Scientists, told us. He conceded that some information previously

available to the public should not have been: "There were

reports available for sale from the government on the production

of biological and chemical weapons that we're better off without,"

he noted. But he added, "It's clear to me that the Bush

administration has gone overboard. It has removed all kinds of

things that ought to remain in the public domain.... The result

is a much more one-dimensional picture of government activity."

Indeed, actions to classify documents jumped

by 44 percent during fiscal year 2001, according to the federation's

Information Security Oversight Office, which oversees classification

programs in government and industry. The public can no longer

access such basic information as the risks associated with chemical

toxins used in local plants or maintenance violations by commercial

airlines. Members of Congress can't even find out details of

how the Pentagon intends to implement the USA PATRIOT Act. In

the meantime, fewer high-ranking officials are available to the

news media -- inquiries and interview requests are being routed

through public affairs offices -- and the Bush administration

has been exceptionally aggressive in cracking down on officials

who have leaked even the most innocuous details to the press.

In effect, the Bush administration has

hamstrung the public's -- and with it, the media's -- ability

to scrutinize governmental and corporate misdeeds.

But the onslaught doesn't stop there. On

Feb. 7, an anonymous Justice Department staffer sent a draft

of a new bill titled the Domestic Security Enhancement Act of

2003 to the Washington, D.C.-based Center for Public Integrity.

The bill, commonly referred to as Patriot Act II, expands on

the government's authority to curb civil liberties in the name

of national security. If implemented, it would codify into law

many of the steps taken by the Bush administration limiting the

public's right to know -- including the withholding of information

on suspected terrorists in government custody, restrictions on

the information the EPA must make available associated with the

Clean Air Act, and immunity from civil lawsuits for corporations

that provide sensitive information to the government, to name

but a few.

The Bush crackdown is working: The administration,

many agree, has succeeded in making it harder to report the news.

Already suffering from downsized newsrooms, reporters spend more

time trying to fight for basic information and pin down simple

details and have less time to analyze the data and its impact.

As a result, they become more susceptible to official spin.

Journalists have also been coming under

fire from sources they rely on to do their jobs. "Reporters

demand access to elected officials and to government officials

in order to do their business," explained Peter Hart, media

analyst for Fairness and Accuracy in Reporting and cohost of

"Counterspin." "If they offend [those officials]

or cross them somehow, they run the risk of losing that source.

There have been reports that this administration has been much

more open about scolding reporters and keeping reporters at a

certain distance if they perceive them as overly hostile or aggressive.

So you have this sense among reporters in Washington that this

administration really doesn't tolerate much in the way of critical

reporting."

But it gets worse. "American journalists

face an increasing likelihood that courts will treat them as

government agents with no constitutional right to keep sources

confidential or to withhold unpublished materials from prosecutors,"

write the authors of the Reporters Committee for Freedom of the

Press report. On July 12, 2002, a U.S. district judge ordered

CNN freelance reporter Robert Young Pelton, who had interviewed

"American Taliban" John Walker Lindh on videotape in

Afghanistan, to testify in Lindh's terrorism trial. The order

became moot when, three days later, Lindh pleaded guilty to the

charges against him; but the judge's published ruling can be

used as a precedent in future cases. "It may only be a matter

of time before government agents descend on newsrooms with subpoenas

for confidential sources, unpublished notes, and video outtakes,"

the report ominously predicts. The report also warns that journalists

could easily become entrapped in antiterrorism investigations

through the expanded surveillance powers granted to the FBI by

the PATRIOT Act.

"The real danger," Hart said,

"is the fact that it's very difficult to reverse these trends.

Once you've set this in motion, it would be hard to imagine a

future administration deciding to loosen the rules and allow

increased access to government business and to government documents."

Not fighting back

In the face of this secrecy blitzkrieg,

you might expect the major news media to be up in arms, fighting

back in the courts and on the front pages.

For the most part, it hasn't happened.

"The No. 1 effect on the media since

Sept. 11 has been to create this atmosphere of overwhelming timidity

on the part of journalists," Hart told us. "They've

understood, in the aftermath of Sept. 11, that patriotism and

unity in the nation was to override journalistic values of skepticism

and inquiry. I think that sensibility took hold in the journalistic

culture in the mainstream right away. It still has a huge impact

on how they're processing information now."

Most recently, Hart said, the media have

paid scant attention to the potential ramifications of Patriot

Act II and have failed to question whether Colin Powell was accurate

in his recent statements to the United Nations calling for war

on Iraq. "These stories haven't been pursued with the kind

of vigor one might expect in a society with a free press,"

he said.

The attitude starts at the top. In a Feb.

25 article in the U.K. Independent, Robert Fisk reports

that CNN has instituted procedures under which all news script

originating outside Washington, D.C., Los Angeles or New York

must be approved by a team of editors at the network's headquarters

in Atlanta.

Implemented Jan. 27, this requirement has

already led to censorship from above: Fisk reports that a CNN

executive recently killed a story by reporter Michael Holmes

on how Israeli troops regularly shoot at Palestinian ambulances

in the occupied territories as they attempt to transport the

injured.

"The reason was we did not have an

Israeli army response, even though we stated in our story that

Israel believes that Palestinians are smuggling weapons and wanted

people in the ambulances," Holmes told Fisk. But the army

had refused to grant CNN an interview. "Only when, after

three days, the Israeli army gave CNN an interview did Holmes'

story run -- but then with the dishonest inclusion of a line

that said the ambulances were shot in `crossfire'," Fisk

wrote. "The relevance is all too obvious in the next Gulf

War. We are going to have to see a U.S. Army officer denying

everything the Iraqis say if any report from Iraq is to get on

the air."

There are glimmers of hope. Media activists

such as Lucy Dalglish, executive director of the Reporters Committee

for Freedom of the Press, see some indications of a turnaround.

"The Detroit newspapers and the newspapers in northern New

Jersey and New Jersey Law Journal challenged the INS policy preventing

any member of the public from attending an immigration detention

hearing," Dalglish said. Now the Supreme Court must decide

whether to hear those cases. "Organizations like mine [are]

co-plaintiffs in a FOIA lawsuit against the Justice Department

trying to find out the identities of the detained. We have participated

with a number of news organizations along the way that have been

trying to make sure we get as much access as possible to what's

going on in the [alleged Sept. 11 co-conspirator Zacarias] Moussaui

case. And Washington bureau chiefs have been working very hard

in trying to make sure we get better access to military units

than we did during Gulf War I."

As a result of mass, worldwide protests

against the drive to war on Iraq -- and public criticism of the

media's downplaying of such actions -- more media outlets were

also doing a better job of covering dissent than they had been

a couple of months ago.

But now that the war has started, the outlook

isn't encouraging.

On the ground

There was a time -- and it wasn't so long

ago -- that aggressive media coverage helped turn around public

opinion on a war. It took a while for the press to get beyond

the pro-military reporting from Vietnam, but when the critical

stories came in, most historians agree, the words and pictures

showing the reality on the ground shook up the nation.

But the government learned from that experience,

too.

"When I first went to Vietnam, I just

wandered around by myself. I didn't ask anybody's permission,"

said syndicated columnist Robert Scheer, who covered the Vietnam

War for Ramparts magazine in the mid '60s and then worked

for the Los Angeles Times for 27 years. "A lot of

journalists, they just checked into a hotel in Saigon and they

went off to look for their own stories.... They gave you a sense

of the madness of it, of the contradictions." Since then,

he said, "they learned how to make these wars appear antiseptic.

War has been turned into a video game.... They've managed to

make war palatable. They've cleaned it up."

Sydney Schanberg, a veteran war correspondent

whose coverage of the war in Cambodia formed the basis of the

Oscar-winning movie The Killing Fields, explained how

the change happened. "After Vietnam," he told us, "there

were two rehearsals on how to deal with the press: Grenada and

Panama." It was during those military campaigns, Schanberg

said, that the Pentagon began creating elaborate rules of engagement

for reporters, limiting access in the field.

Those rules were toughened during the first

Gulf War and in the Afghanistan conflict. On Oct. 7, 2001 --

the day the United States began dropping bombs on that faraway

nation -- the U.S. military prevented the media from obtaining

footage of the campaign by purchasing exclusive rights to private

satellite imagery of Afghanistan, although its own satellites

provided better resolution. At one point, "Marines quarantined

reporters and photographers in a warehouse to prevent them from

viewing American troops killed or injured by a stray bomb near

Kandahar," according to the Reporters Committee for Freedom

of the Press's "Homefront Confidential" report. Not

until March 4, 2003, did the Pentagon allow reporters to accompany

U.S. soldiers into the field.

Distressed by the lack of access during

Gulf War I and, more recently, the U.S. campaign in Afghanistan,

major media outlets began lobbying for more openness. As a result,

the Pentagon issued a set of rules for war coverage in the campaign

against Iraq that include the current "embedding" of

approximately 500 reporters with U.S. troops. The new regulations

have been hailed as a victory by mainstream media. But when you

look at what the rules really say, the picture isn't so pretty.

"On paper it looks like a considerable

improvement," Schanberg said. "For example, there's

no auto review of copy by the military." On closer inspection,

however, Schanberg found reasons for concern. All reporters "embedded"

with U.S. troops must sign a contract agreeing to the Pentagon's

rules governing coverage. Included in the document is a clause

dictating what kinds of information reporters can and cannot

detail. Journalists can be precluded from reporting certain "sensitive"

information according to the military commander's discretion.

What's more, "all conversations [with

the troops] must be on the record," Schanberg said. That's

a big problem: In the Vietnam era, much of the most damning information

came from military sources who would talk to reporters if their

names were not used.

The Pentagon can revoke a reporter's credentials

at any time, for any reason.

Schanberg, who now writes for the Village

Voice, argues that ultimately there should be as many reporters

-- if not more -- working on the ground in Iraq independently

of the U.S. military as there are stationed with the troops.

Also, some worry that placing reporters with U.S. troops -- indeed,

having them undergo similar training and wear similar gear --

creates a heightened identification with the soldiers that could

slant coverage of the war.

"Embedding is bullshit," Scheer

insisted. "You're just getting swept up into a big, mass

machinery. They're just giving you photo ops. It's when you get

away from the crowds, stick around and talk to people that you

get the real stories. Otherwise, you're just being led around

by the nose."

Most of the coverage of the buildup to

war centered on troop movements and possible war scenarios interspersed

with flag-wrapped fluff pieces such as ABC's ongoing "Profiles

from the Frontlines" series. Ultimately, the critics interviewed

for this story would like to see reporters ask tougher questions.

"The real story will be, where's the

threat?" Scheer said. "Is it manufactured? Will reporters

go after that?"

Schanberg's big question is, what happens

afterward? Like Fisk, he'd like to see more contextualization

of the issue: how did we get here, and what lessons might we

learn from the past?

"Why didn't journalists say, hang

on here, I thought bin Laden was the guy we were after,"

Fisk asked. "What's Saddam got to do with Sept. 11? But

the media in the United States just went along with the new version:

`OK, today it's Saddam Hussein week,' and that's how it went....

We need to use some kind of morality instead of presenting everything

blandly and accepting what American officials and intelligence

analysts say."

Hart and Dalglish agree there's no good

reason reporters shouldn't do more to take the Bush administration

to task. "I'd like to see more newsrooms, when they're told

they can't have access, to write about it ... and let the public

know what the impact of that action is," Dalglish said.

Ultimately, it's up to the media and the

public as to how much secrecy and control we'll accept -- and,

in general, to what degree we'll consent to toeing the Bush administration's

official line.

IN

THE NEWS | CALENDAR

Comments?

© Copyright 2003, North Coast

Journal, Inc.

© Copyright 2003, North Coast

Journal, Inc.

|